Will It Zwerch? Landmarking in Video Analysis

Lots of people look at fencing. Lots of people watch videos. What are you actually “looking” at when breaking down someone’s motion?

Lots of people look at fencing. Lots of people watch videos. What are you actually “looking” at when breaking down someone’s motion?

Combat Con 2021 just wrapped up recently*, the first large-scale North American event to start back up since the Covid shutdowns. It is also a […]

You see the title.

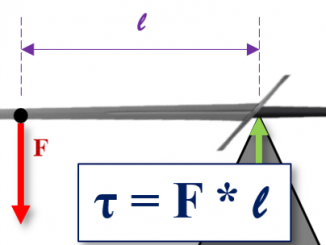

I’ve harped about Moment of Inertia in multiple articles. Now I try a new experimental method for figuring it out.

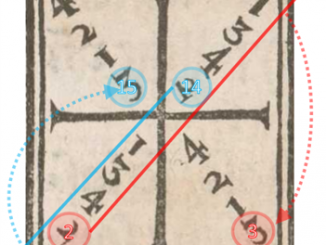

I don’t like remembering arbitrary sequences. And on the surface the 16-cut pattern that forms the Meyer’s Square is the exact type of arbitrary sequence that I hate. But is it really?

There have been a number of very good physics descriptions of sword motion. However they neglect the most important part: a sword isn’t free floating in space!

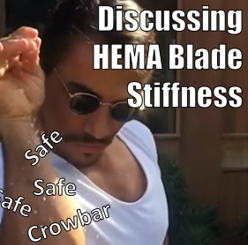

We frequently talk about how to make swords “safe”. Unfortunately unless you can come up with a definition which satisfies a few specific criteria, the word “safe” doesn’t have a lot of meaning.

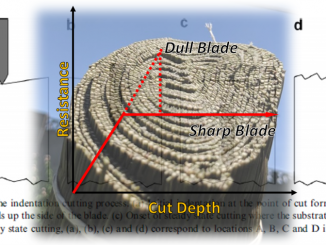

From a blade resistance point of view, cutting actually has two distinct phases: the internal and external.

Two of the most popular ways to quantify blade stiffness are the SCA Flex Test and the Buckling Test. Unfortunately they both have issues, but we’re suffering for lack of better solutions.

“In your opinion, which country has the highest level of practitioners?” Let’s see if I can answer this in the most unhelpful way possible.

Copyright © 2026 | WordPress Theme by MH Themes