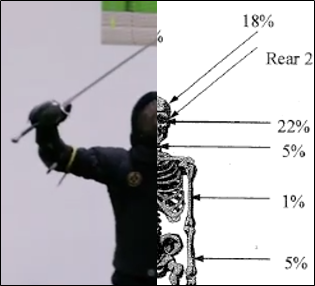

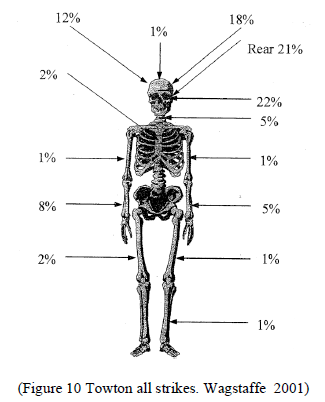

In 2011 Johann Keller Wheelock Matzke submitted a dissertation entitled “Armed and Educated: Determining the Identity of the Medieval Combatant”. This is a great read for anyone interested in the historical context of HEMA, but of particular interest to the STEM nerds out there is his Chapter 4: Injury pattern in the archaeological record. In this chapter we are presented with injury data observed in skeletons from historical battles.

Lets see what how this compares to modern HEMA tournaments! For reference I am using the Longsword tournaments from SoCal Swordfight 2019 (1,312 exchanges) and Longpoint 2019 (661 exchanges). Both of these events keep track of hits by target area, and I have written about each of them in the past.

- Data Mining – SoCal Swordfight Longsword

- Is Going For Deep Targets Worth It and More – Longpoint Stats Review

Limitations

There are some limitations to the data presented in Armed and Educated, which should not be a surprise to anyone. Matzke explains these in significant detail, with each archaeological find having its own caveats. Some highlights:

- There is a different context for each of these historical finds. Tactics, weapons, armor, and combat situations are not the same.

- The data only records injury by sharp trauma. This means that and piercing (arrows) or blunt (clubs, maces) trauma is not included in this data.

- Only injuries to the skeleton are recorded. Any soft tissue is long gone.

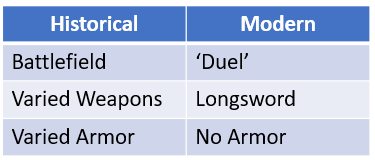

It is also a bit disingenuous to try and map these historical finds to modern tournaments as if they are the same thing. Even given the obvious (that modern tournaments are sportive games as opposed to fights with real weapons) we still are quite a few steps separated. For instance, modern intent is generally to practice unarmored combat, and equipment is only worn for safety.

The Data

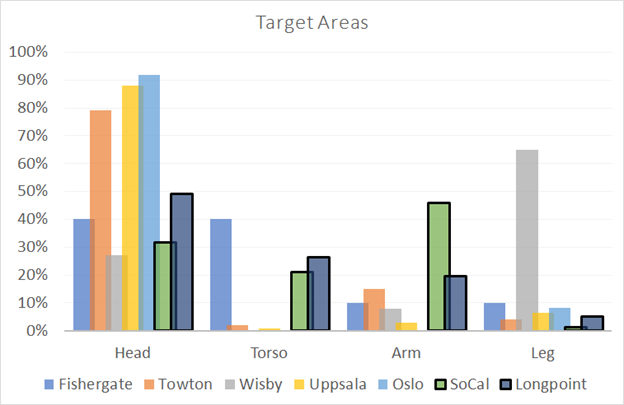

Ta da! Here is a plot of the 5 historical sites, and the two modern tournaments. (Read the paper for more information on where/when these battles occurred.)

And before we start I will remind you again: we have to be reeeeeally careful what we can draw from this.

Head

We all know that historical sources say to target the head above other targets. This data just hammers home the point. Nothing interesting here.

Leg

The leg shots are (generally) on the low end of both the historical record and modern tournaments.

The interesting outlier is the Wisby data, with a whopping 65% of cuts landing on the leg. Matzke suggests the shields worn as a possible explanation, and I’m not a historian enough to either support this explanation or offer one of my own. But suffice to say that comparing this to modern longsword tournaments is not all that enlightening.

Torso

The data from these sites shows an exceedingly low number of torso strikes, both in comparison to modern tournaments and in general. There are two main factors which could be contributing to this:

- Any cuts below the rib-cage would not leave skeletal marks unless they were deep enough to reach the spine (very difficult) or low enough to reach the hip bone.

- Going by historical sources there is a preference for utilizing thrusts rather than cuts against the torso. If this is reflective of the actual injury patterns we would be less likely to see evidence of attacks to the torso. (Learn more: How Did The Sources Say We Should Weight Targets?)

This doesn’t come close to explaining the large disparity. While the sources say that we should be thrusting the torso rather than cutting, HEMAists don’t tend to be good at taking that advice. SoCal 2019, for example, still had 60% of torso shots recorded as being cuts.

So, for those of you keeping score on cuts to the torso:

✓ No support in archaeological records.

✓ Not a preferred target in historical training documents.

✓ Modern tournament data suggests they are unsafe (Learn More, and More)

✓ Modern test cutting shows a big disparity between the technique needed to make a torso attack function as a cut, and what people actually throw when sparring.

Arms

This is the really interesting one: the extremely low incidence of attacks to the arms. In modern practice we tend to see the arms/hands as one of the highest targeted areas. And this isn’t as easily explained away with soft tissue vs skeletal damage. In the arms, and especially in the hands, the bones are quite close to the surface and would likely not escape froma sword cut unscathed.

My best hypothesis is that this shows the difference between single and battlefield combat. When two individuals face each other they have a significant amount of time to try to engage on their terms, and they are very careful to manage distance. Because of this the hand/arm becomes a prime target, one that can be reached without exposing your body to an opponent’s attack. This requires both time to be patient, and space in which to maneuver. Both conditions which would be lacking on a battlefield.

But this is pure speculation.

Conclusion

Hit the head more and cut to the torso less? Have we heard this somewhere before?

Stats for Nerds

| Fishergate | Towton | Wisby | Uppsala* | Oslo | SoCal | Longpoint | |

| Head | 40% | 79% | 27% | 88% | 92% | 32% | 49% |

| Torso | 40% | 2% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 21% | 26% |

| Arm | 10% | 15% | 8% | 3% | 0% | 46% | 20% |

| Leg | 10% | 4% | 65% | 7% | 8% | 1% | 5% |

*The data provided from Uppsala doesn’t add to 100%.

Bibliography

[1] Johann Keller Wheelock Matzke. “Armed and Educated: Determining the Identity of the Medieval Combatant.” Master of Philosophy in Archaeology, University of Exeter, UK, 2011 https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10036/3729/MatzkeJ.pdf?sequence=2

[2] Wagstaffe, C. (2001) “Were Warriors Trained to Fight?” Unpublished MSc dissertation, University of Bradford.