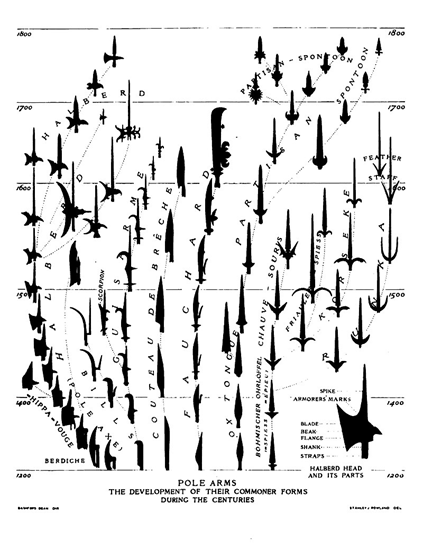

Knights = Swords. It’s common knowledge for most people. But us learned types know that the sword was more of a civilian weapon than the main personal arm of war. That honor goes to polearms.

But why aren’t they more well represented in modern HEMA? Obvious reasons off the top of my head, are the availability of historical sources* and the prevalence of the sword in our modern consciousness. But I suppose an additional reason**: that you can’t spar at intensity with them.

Tournaments and sparring are a big draw that is helping to create interest and bring people into the art. And if you can’t play safe with something in the same way, you can’t get the same exposure. But why is a polearm so different? Let’s have a look.

*that isn’t to say that there aren’t plenty of sources. But in the dark pre-wiktenauer days it wasn’t so simple to get your hands on translations to fit your personal flair.

** In the un-scientific speculatory sense that you’ve come to not expect from this publication..

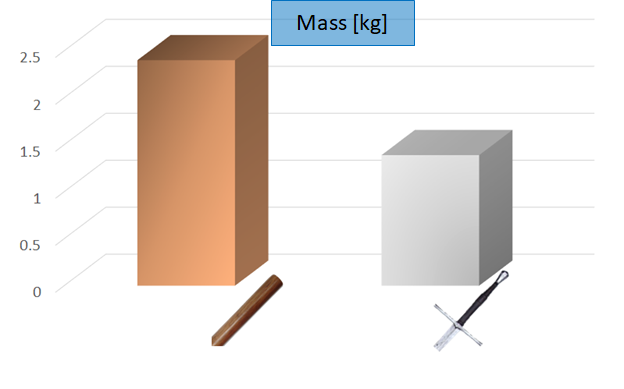

Weight

For our generic staff, I’m going to use a 1.5” (3.8 cm) thick oak rod that is 3 m (~10’) in length.

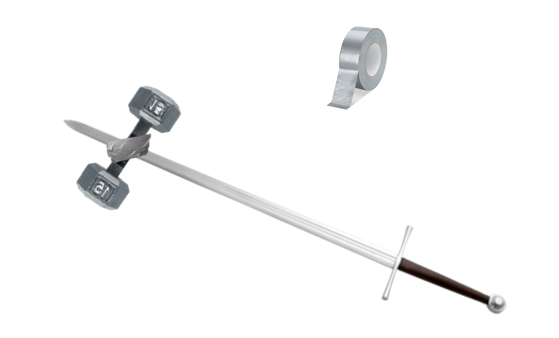

The oak staff is heavier than the steel sword, but not by an enormous margin. Have a slightly thinner staff made out of a lighter material and you can level the playing field. Have a heavy sword and you can make probably edge out the staff. But weight isn’t the most important quantity at play here.

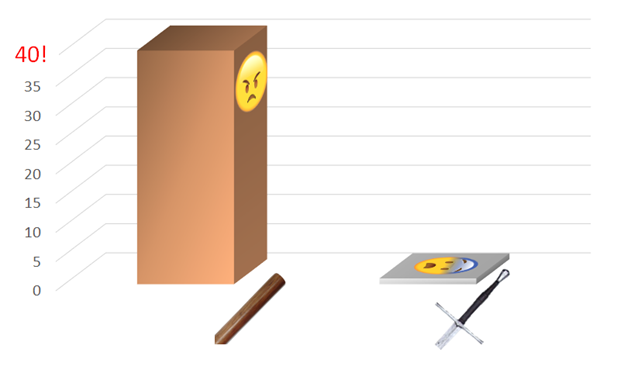

Moment of Inertia

Moment of Inertia is kind of like how heavy something is, but in a special kind of heavy that affects how it rotates. Click here to learn more!

Let’s consider a longsword as having a moment of inertia of 1. Now let’s compare it to the staff…

Now, the number 40 is kind of arbitrary. I’m using the Albion Crecy as a reference, which isn’t a particularly large or heavy longsword. Additionally it doesn’t factor anything about how you transfer force from your body into the sword, or how you hold it. But the bottom line is that the staff has a LOT more behind it. If you swing it at the same speed, it’s going to come in a lot harder.

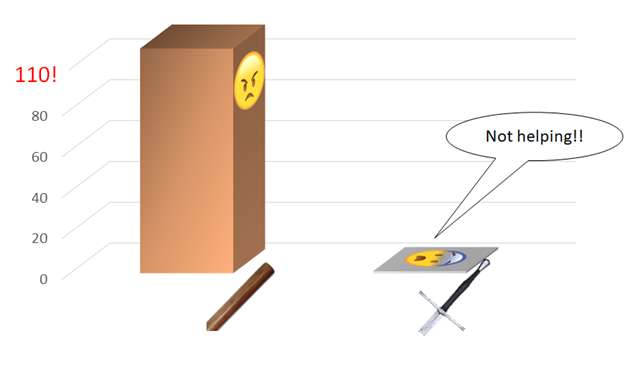

Thrusting

Another fun feature of polearms is that they are extremely unforgiving in the thrust. The moment of inertia is a measure of how stiff something is in the thrust. But not the first moment of inertia we were talking about. It’s the second moment of inertia. (I’m not joking).

Let’s compare my trusty feder, with a ‘stiffness’ of 1, to the same oak staff.

That certainly didn’t make things better. The staff is now over 100 times as stiff in the thrust!

Relative Stiffness

One thing that can throw people off when thinking about staff weapons, especially ones made out of more flexible materials such as ratan, is how much they can flex under their own weight. Take a spear and wobble it back and forth and you may see the end flopping around a lot more than you are used to with a sword (or you may not, it all depends on what the shaft is made out of).

But don’t equate relative stiffness with stiffness! A quick example:

- Take a sword and wiggle it.

- Now take the same sword and throw a weight on the end.

- Wiggle it and you will see that it seems more ‘floppy’. But do you really think that the sword with a weight strapped to the end is in any way safer to use?

A heavier/longer weapon can often feel more ‘floppy’, because its own weight will cause it to experience far higher forces when it’s moved around. And usually when you hear the phrase “far higher forces” you shouldn’t be thinking “this seems safer”.

Conclusion

This article has all been framed in the context of high intensity sparring, the hallmark of which is that you have protective equipment so that you can work against your partner with a high level of intent. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a ton of very safe training you can do with pole weapons. The fact that you hold the grip so far apart affords you to be able to exert more force decelerating the weapon, mitigating some of the problems. But at the end of the day you have to exert a lot more restraint in your actions. Making it much, much harder to verify that what you are doing actually works if someone has it out for you in earnest.

The numbers I used in this article were a little wishy-washy. For instance: a feder changes its thickness along its length, which has significant effects on the stiffness. And our big bully Mr. Oak Staff doesn’t even have a head attached. You better believe having a steel spike on the end is going to make it hit harder. The main takeaway is that even though the the polearm can feel close to a sword in weight, this does not mean it is anywhere near as safe to use in sparring.

Stats for Nerds

Albion Crecy Longsword: 0.11 kg m/s2 at the cross, .18 kg m/s2 at the pommel

1.5” x 3 m Cylinder = 3.42e-3 m3

Density of Oak ~= 700 kg/m3

Mass of Oak Staff = 2.4 kg = 5.3 lbs

Moment of Inertia at Base = 7.2 kg*m2

Feder second moment of Inertia = 51.9e-12 m4

Feder stiffness = (200e9 N/m2)(51.9e-12 m4) = 10.4 N m2

Staff second moment of inertia = 103e-9 m4

Staff stiffness = (11e9 N/m2)(103e-9 m4) = 1133 Nm3

All my longsword measurements came from my previous articles and… Wait, does this mean I can cite myself and act like I have real sources?

Bibliography

S.C. Franklin, “What makes a sword stiff?,” Sword STEM, 17-Oct-2018. [Online]. Available: https://swordstem.com/2018/10/17/what-makes-a-sword-stiff/. [Accessed: 01-Mar-2019].

S. C. Franklin, “How Fast Do Swords Move? – Try 1,” Sword STEM, 22-Aug-2018. [Online]. Available: https://swordstem.com/2018/08/22/how-fast-do-swords-move-try-1/. [Accessed: 01-Mar-2019].