If you’re reading this you’ve either made it to the end of the article series on Ecological Approaches to Coaching, or you just skipped to the end because you wanted the TL;DR. Fortunately I think this article will be able to please both crowds.

This is Part 7 of my series on Ecological Approaches/Psychology. The article stands alone, but is part of a broader modern understanding of human action and perception.

- Part 1: Ecological Psychology

- Part 2: Motor Solutions

- Part 3: Affordances

- Part 4: Direct Perception

- Part 5: Perception-Action Coupling

- Part 6: Control Laws

- Part 7: Implications of EA (you are here)

Summary Of Concepts

The main points to understand about the Ecological Approaches, when put into actionable coaching items, are as follows:

- You don’t need to practice a motion to learn how to do it. Nor does practicing in isolation/controlled settings lead to improved learning speed or retention. In essence there is no need to “drill” skills, you can learn them through actually having to spar.

- Realistic information and feedback are super important to learning. Having a setup where someone can “drill” is not realistic and will teach them to perform a choreography of the technique, rather than the technique.

- All movements are unique to the time and place they are used. Rather than trying to teach someone “what to do” you essentially are teaching them “how to get your body to do what it needs to do” from any position. These unique motor solutions are generated subconsciously, with the individual focused on the overall goal and not the method.

- People are really bad at things like “how far?” but pretty good at “can I hit?”. All coaching and training should be related to a goal or outcome, rather than something like body position or movement pattern.

- “The body shows remarkably little interest in what the coach has to say!”; don’t tell people what to do and instead give them an objective to achieve.

- Learning is non-linear, and not always obvious. The methods which show the biggest improvement from the start-to-end of a class usually have the worst long term learning, and the methods which are more random can show much better retention.

Which is not to say you can’t learn things in a traditional way. People obviously are doing it all the time. However far more of the “learning” is actually coming from the sparring than the drilling.

Theory vs Practice

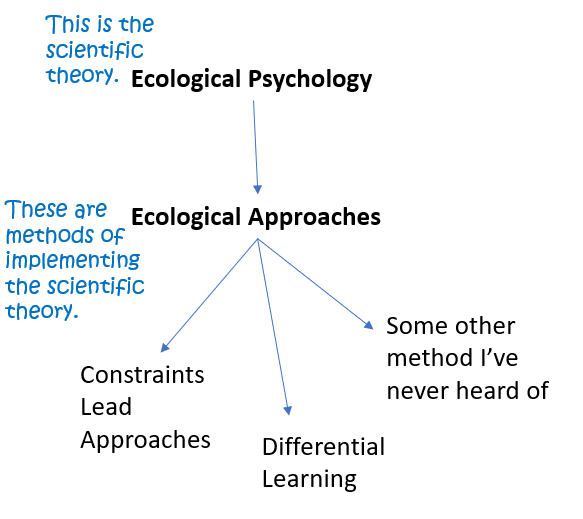

These articles have been about the science that underpins the Ecological Approaches to Coaching, the field of Ecological Psychology. I’ve been a little lax on how I use terms, so here is some clarification:

Is a detailed knowledge of the scientific theory necessary to understand the actual implementation? In most cases probably not. Knowing exactly how degrees of freedom and muscle synergies work is unlikely to be relevant.

However, knowing that you don’t need to teach someone a motion in an idealized and isolated form is hugely important! When I first started down the coaching road that led me here I was adding increasing levels of variability. I was nevertheless a little concerned that I’d somehow be teaching people “bad habits” or just “wrong” by not taking enough time to get it right. Learning that it wasn’t a necessary step freed me from that shackle and allowed me to continue down the road of improving my coaching implementations.

Implementations of EA

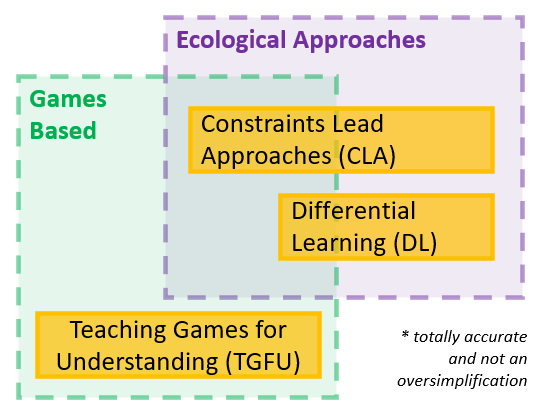

The main implementations of Ecological Approaches are Constraints Lead Approaches and Differential Learning. Contrary to what you may think from the Game Design 4 HEMA crowd, Ecological Approaches does not necessarily imply games-based training. Games-based is just one way you could implement EA, and in fact you could do game-based in a completely non-ecological way.

And as I’ve said many times before, SwordSTEM is not a coaching blog. If you want ideas on how to actually use any of these effectively you can head on over to gd4h.org. The most important part is to remember that these non-linear, non-prescriptive steps are not meant to support the traditional learning of skills, they can replace them completely. Give it a try and see!

Constraints Lead Approaches (CLA)

Constraints Lead Approaches (CLA) are methods where you develop and refine movements by adding training constraints that force new adaptations. For instance, if someone is constantly attacking with their hands too low you don’t correct it directly. Instead you add a constraint that will cause attacking with hands low to no longer be effective. Something like making them struggle to get enough distance (which will cause them to raise their hands instinctively as they try to reach) or having to attack against opposition (which will cause them to raise their hands so as to not get hit in the face).

For fencing, the opponent is overwhelmingly the most important feature in the environment, so most reasonable constraints will end up revolving around them. Hence the games-based training, to ensure representativeness from the training environment. But that doesn’t mean CLA can only be done with games, just that games are probably going to be the primary expression of this approach for a 1v1 combat activity.

Differential Learning

A way to understand Differential Learning is kind of like machine learning for computers. If you want to get a computer model to learn how to perform a task you don’t feed it the same couple of ‘ideal’ examples over and over. You give it as big a learning data set as possible. Which is close enough to the idea of how Differential Learning works.

Rather than train the exact task, you train to do a whole bunch of similar but random tasks/motions. The idea being that you are building a “mapping” between the motor solutions your body constructs and the ultimate performance outcome. So think less: “throw the ideal opening attack 100 times” and more: “do 100 attacks each with a different starting position and equipment, most of which are completely unrealistic”.

Teaching Games for Understanding

I’ll also briefly touch on Teaching Games for Understanding, TGFU. This is a practice of using games to underpin the concepts being taught in a more conventional manner. The games being an aid to the learning process, rather than being able to stand alone as the actual learning itself.

This is not really an Ecological Approach, as it isn’t based on Ecological Psychology. Using TGFU, you wouldn’t go back to the fundamental concepts of EA to decide how to help an athlete with a particularly challenging issue, or to plan out a curriculum. That said, the differences are going to manifest in how a coach plans; if you walked into a practice that was running games and were asked to say if it was CLA-Games or TGFU, good luck!

How To Coach Good

Seriously though, even though EA tends to show more benefits for coaching education, it isn’t a magic bullet. People still need to invest a lot of time and effort. Coaches need to be attentive to the student’s needs and design training accordingly. An excellent coach using traditional coaching methods will have fighters who destroy those prepared with poorly implemented EA training programs. At the end of the day effort and attention will always be needed to improve.

So while this hasn’t been about exactly how you can use EA to help improve your teaching, I’ll close with some suggestions on implementation:

- Don’t take everything here as gospel right away.

- Pick one thing that you want to teach. Something that is rather tricky or takes a long time to learn.

- Try to develop the skill with EA training methods for a few weeks and look for improvement.

- If you like what you see, expand and pick another part of your curriculum to transition over.

I am really not a fan of trend chasing, and I feel that having anyone throw all their hard-earned experience out the window is always a bad idea. I got to where I am now by slowly testing out the waters and making sure that every step was an improvement, and that what I was implementing with this crazy new “instruction-less teaching” was always an improvement over what I was doing before. It’s certainly a challenge at times, but a very rewarding one.

Finally Done!

It only took me 6 months, but I did it! This is an article series I’ve been sketching out for quite some time now, but between event travel and event organization it has been a long time coming. But, it’s not like I promised anyone I’d have it done in a timely manner or anything…

Stuff For Nerds: Attractor States

The following is a neat principle that I just didn’t think was core enough to justify in the main body of these articles. Because, from a coach’s point of view, all of the following nerd stuff simply translates to: “breaking habits requires a lot of work”. But, if you are still here, away we go!

An attractor is some configuration that has a natural attraction, a definition I’m sure you are glad I was able to provide. You can kind of think of this like a habit; it is a movement pattern that you are drawn to.

If you’ve ever tried the classic challenge of patting your head while rubbing your belly you’ve seen attractor states at work. We normally want to bring the hands in-synch when doing something, and if you try to go faster your body naturally brings them towards this state without you thinking about it.

The example I used in the Speed Coordination section of Slow is slow and fast is fast. And don’t let anyone tell you otherwise is a very good illustration, so I’m going to reuse it.

Did you know that the body likes to coordinate things differently at different speeds?

There’s a speed-dependent mechanics transition that we are all familiar with: walking to running. Below a certain speed the running motion is just plain awkward. Above a certain speed you will find it very hard to keep a walk from breaking into a jog. Maintaining the walking form without allowing any running form to creep in is one of the hardest things in the sport of speed walking. (Yes, speed walking is a sport. It is an Olympic event and they can walk faster than you can ever dream of running.)

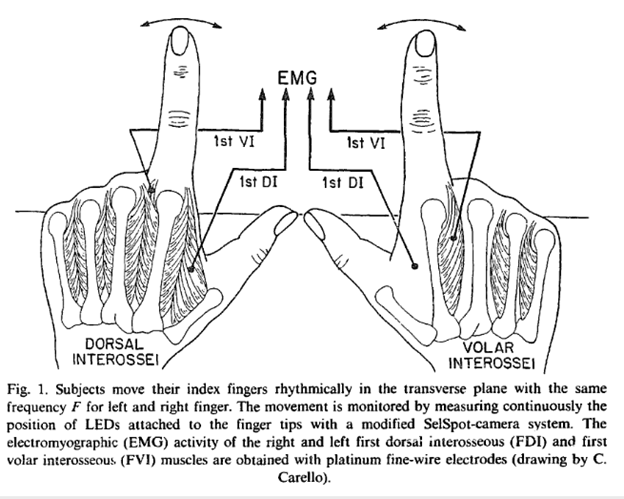

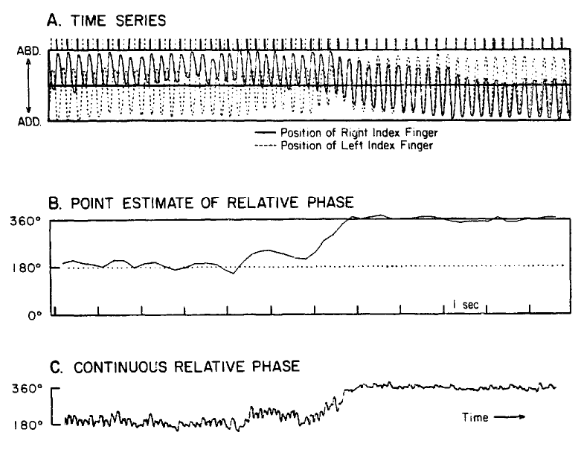

Not only does the speed of movement affect the movement pattern, but it affects how you coordinate both sides of your body. Take this cool experiment:

Participants were asked to move their fingers back and forth in time with a metronome that was gradually speeding up. All participants began moving their fingers out of phase, that is to say they moved their fingers towards each other then apart. But at some point as the speed kept increasing they spontaneously switched to keeping the fingers in phase, with the fingers moving in tandem. This is an example of the body displaying two different movement patterns as it transitions from slow to fast motion.

It’s crazy that your body can jump to doing a completely different thing just because you change the pace at which you’re asking it to do a task! Ever notice how in Sword and Buckler tournaments people quickly start moving their sword and buckler completely independently, and in a very different manner than they exhibit when performing drills? It’s because once the intensity is kicked up a notch their body starts relying on completely different movement patterns. And if they haven’t trained those high speed movement patterns… you can have a pretty good idea how artful it ends up looking.

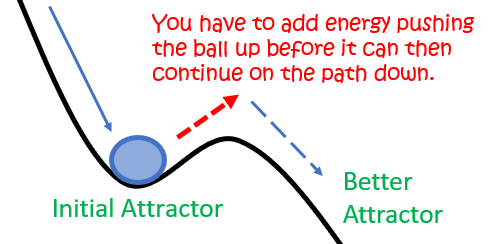

In order to break an attractor state you need a lot of work to, essentially, develop a new attractor state. Once the new state has been learned it is very stable, but getting to that point can be difficult.

You can imagine rolling a ball down the hill. If it gets caught in a rut (attractor #1) it isn’t going anywhere – even if gravity would want it to keep moving. You have to intervene, by adding energy to lift the ball, to get it to move towards the ground (attractor #2).

So if you have a student with something you want to correct you need to create a scenario where the current attractor state is no longer an attractor, and allow them to move on to a new (and presumably better) one. Because people change form when they need to, not when a coach tells them to.

“The body shows remarkably little interest in what the coach has to say!”

– Frans Bosch