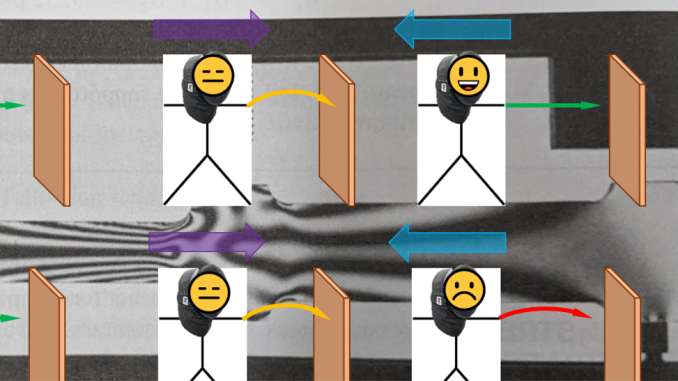

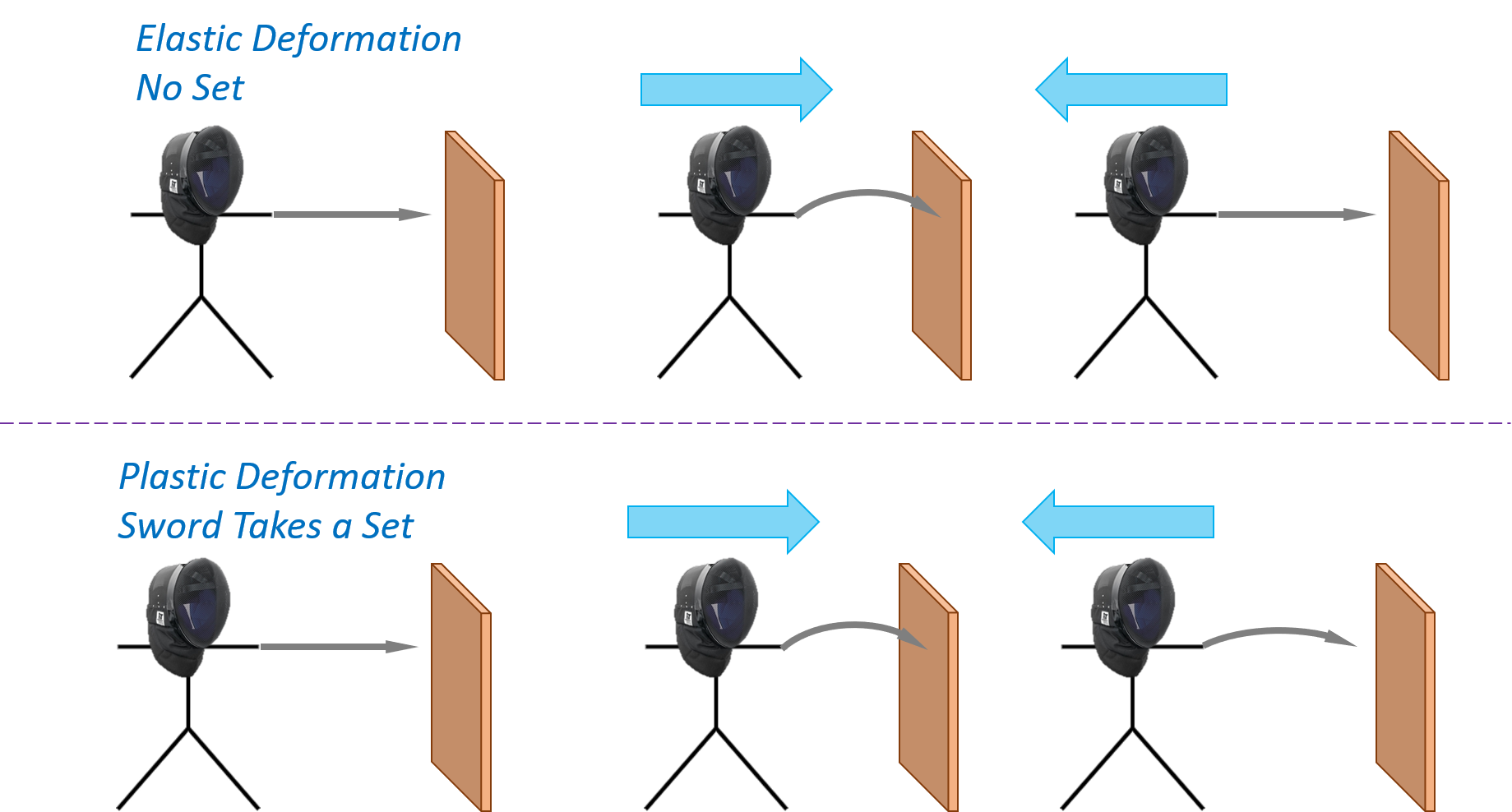

Ok, that is a loaded headline that is going to get some attention. But before we start, what is a “set” in relation to swords? The short answer is that a set is when a sword has a permanent bend to it. To understand in more detail, we must understand Elastic and Plastic deformation.

If you flex a sword, that is deformation. If you release the sword and it goes back to its original shape, it is an elastic deformation. If you release the sword and it doesn’t go back to straight, then it is plastic deformation. (Introduction to Material Properties) What we refer to as a “set” is plastic deformation, a blade with a curve to it.(Why Does My Gear Crack in Half?)

Let’s get this out of the way right away: this is not an article about metal fatigue in relation to how long a blade will last. David Farrell did a good analysis of that already, and it has much more technical detail than I ever go into (To Straighten Or Not to Straighten: That is the question!).

This article will focus on the safety implications of using a blade with a set in it. After all, I’ve never really understood the point of “don’t use that sword, it might break”. Well, if the downside of a sword breaking is that I don’t get to use it again, and you are telling me not to use it again, isn’t that effectively the same thing? The only difference is that I get more life out of one than the other.

However, if using a sword with a set in it was somehow unsafe, that would be a different matter. But, as the tag line for the article suggests, reality is often the opposite of what people expect. (This is why engineers don’t have any common sense. Their training has taught them that it is so often wrong.)

Stress Concentration Factors

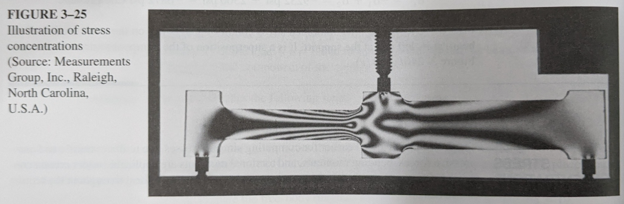

Part of the conventional wisdom associated with bent swords has to do with an intuitive understanding of stress concentration factors. And what, you may ask, is a stress concentration factor? Simply put, they are anything that creates a localized region of higher stress in an object.

One physical feature that causes stress concentrations is sharp edges. You may have heard how in the early days of airliner design they had rectangular windows, only to find that this was a failure point due to the higher stress on the corner. Which is how we arrive at the rounded window shape we are accustomed to.

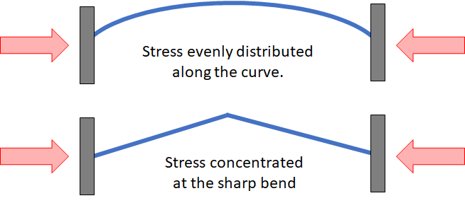

A sword with a sharp set will have a stress concentration around this sharp bend. Any time the sword is flexed the sharply bent region will experience more force than the rest of the sword, which means that it will break that much sooner.

So if you see a sword with a sharp bend, it is not a particularly good sign. You can try to straighten it out, but without professional tools you will have limited success. Even if you get the blade mostly straight there will still be the stress concentration region, significantly lowering the life expectancy of the blade.

A sword with a sharp set will take more stress than a straight sword when flexed, but a sword with a gradual set will not take any more stress than a sword with no set.

If you have a sword with a sharp set in it, the days are probably very numbered. Even if you can keep fighting with it, you should probably be putting in an order for a replacement. A gradual bend, on the other hand, doesn’t really tell you much about life expectancy. You haven’t introduced any stress concentrations to artificially lower the life of the sword. And you may have actually done a little quality control on the blade without knowing it…

Infant Mortality

What is more likely to break:

- An engine that is brand new.

- An engine that has been running for a year.

Common sense would dictate that the engine that has been running for a year has had more wear and tear, and therefore is more likely to fail. But, the opposite is more likely! The engine that has been running for a year has basically proven that it works, but the brand new one is unknown. It is entirely possible that there is some tiny defect in the manufacture of the new part that will cause it to fail very quickly after deployment, an effect that is known as the Infant Mortality of a part.

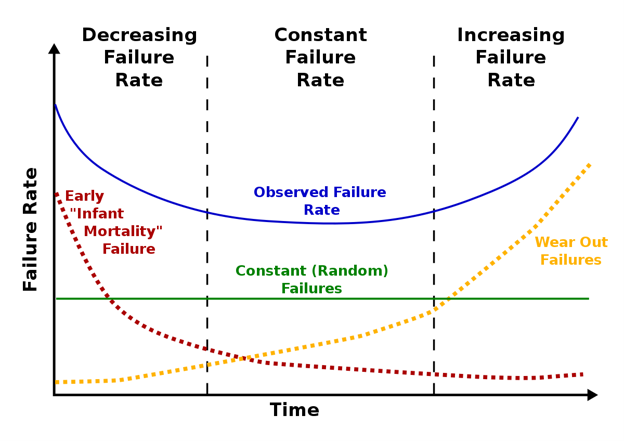

Because of this we actually see that new parts are typically more likely to fail than mid-life parts. Keep in mind that nothing lasts forever, parts will eventually wear out. But the pattern of parts failing early is well documented. Replacing old parts before they show signs of failure is actually correlated to worse reliability in many fields!

How does this apply to a sword with a set in it? When a sword bends past its elastic limit it has two choices: deform plastically (take a set) or break. When our sword takes a set we get bummed out about it, but we also forget that we learned something very important: the sword didn’t break when stressed!

|

Aside: The actual shape of the infant mortality failure curve is highly dependent on the type of parts/use cases. The predominance of infant mortality, random, and wear-out failures can produce several different shapes of failure curves. In some cases the infant mortality, or the random failures, could be negligible. I used to do engineering work on the reliability of rotational bearings, and they don’t actually have a ‘wear out’ failure mode! |

Failure Modes

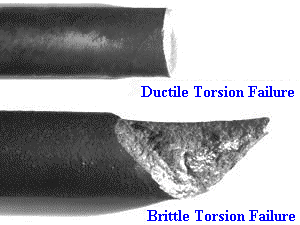

I’ve already covered ductile/brittle in depth in another article (Brittle vs Ductile and Swords in Freezers), but here are the Cliff Notes:

- When ductile things experience high stress they tend to experience deformation, both elastic and plastic (aka a sword taking a set).

- When brittle things experience high stress they tend to just break.

When your sword takes a set, you have confirmed that it is, in fact, ductile. This means you can reliably expect it to continue to take sets in the future if you over-stress the blade.

If, on the other hand, your sword has never taken a set you have no idea how it will react when pushed past its limit. Assuming your blade is made by a reputable manufacturer it is highly likely to deform plastically instead of breaking. But you never really know. Manufacturing processes and quality control around steel quality and heat treating are difficult. All manufacturers have bad blades produced on occasion, and tiny irregularities in the heat treat will result in stress concentrations in the blade.

Knowing your sword is ductile will also give you predictive powers as to how it will break. A ductile blade will break clean, a brittle blade will break jagged.

It doesn’t mean you should expect a jagged break from a sword without a set. It is that you don’t know what the break will look like – the best you can do is make a guess based on the quality track record of the manufacturer. The sword with a set in it, on the other hand, is almost certain to break clean.

Conclusion

It isn’t unsafe to fight using a sword with a set in it.

The sword has proven itself ductile, which is more than you can say abou a sword that has no set in it. While it may be showing accumulation of metal fatigue, this is in no way a safety issue. So keep running with your trusty blade, until it meets a spectacular demise!