Steel is kind of an essential part of sword fighting. It’s what swords are made of*. Naturally, its physical properties are kind of important to the whole process. But what makes it a good material to use in swords? Let’s have a look.

It will also be helpful if you are somewhat familiar with material properties: Introduction to Material Properties

Strength

I’ll start with the first: strength. To get the maximum utility, a sword should probably be able to withstand forces without taking a permanent bend/break[citation needed]. So what materials are strong enough to make swords with?

Well, technically just about anything is. It just changes how much material you need to make the sword with. I touched upon this in my article about Blade Stiffness: you can compensate for a weaker material by simply adding more of it.

Though steel is 3 times stronger than bronze, a bronze rod 1.5” thick will be stronger than a steel rod 1” thick.

Strength to Weight

The problem is, that 1.5” bronze rod weighs over two and a half times as much as the steel one. Maybe just making things thicker isn’t the only way to go about this…

This is one of the reasons why production of steel turned people away from bronze swords and on to steel ones. The steel allows you to use less material to get the same strength. You can make the sword longer, or make it thinner for the same length. Similar improvements in steel quality in the Renaissance allowed for longer, thinner bladed swords, such as the rapier.

The property we are talking about is a material’s strength to weight ratio.

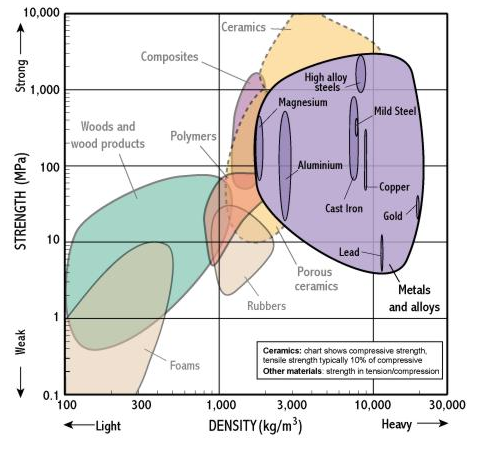

And we if we look at a handy-dandy materials selection chart we can see that High Alloy Steels look relatively good in comparison to things like Mild Steel*, Cast Iron, and Copper (and really good in comparison to things like Lead and Gold).

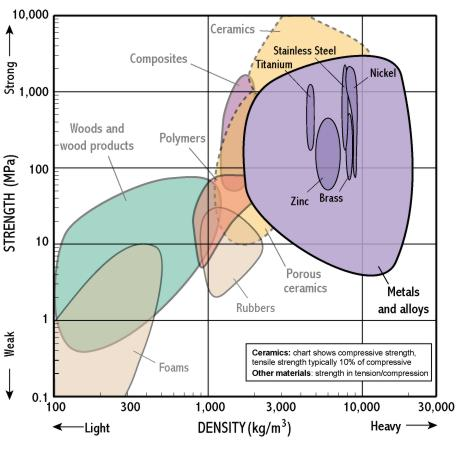

But the chart also gave us some other options. Stainless steel and Titanium? What about aluminum? While not as strong as steel, aluminum is lighter. In fact, aluminum actually has a higher strength to weight ratio than steel. This is why it’s popular for the transportation industry.

*Mild steel is steel with a lower carbon content. It is used heavily in construction because it is much easier to mass produce.

Hardness

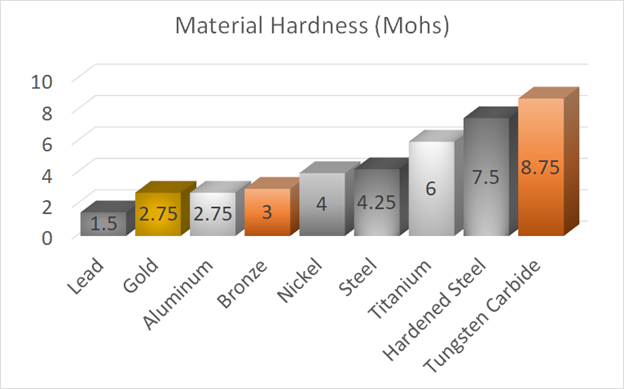

If you are making a sword to cut something, it needs to be sharp. Your most important property here is the hardness of the material. It’s harder to compare the hardness of materials that have a large range of hardness between them. By the nature of tests you tend to use different tests on different materials, but I can break it down for you:

| Foams, Woods, Polymers | Not Hard |

| Metals, Ceramics | Mostly Hard. (seeing as we already eliminated gold and lead…) |

Unfortunately that foam super sword you have been planning just isn’t going to hold a sweet cutting edge.

So the hardness requirement mostly limits us to metals. But even within metals there are variances.

This shows one of the reasons that aluminum isn’t as desirable as steel — it is considerably softer, and won’t hold an edge very nicely. So scratch aluminum from the list.

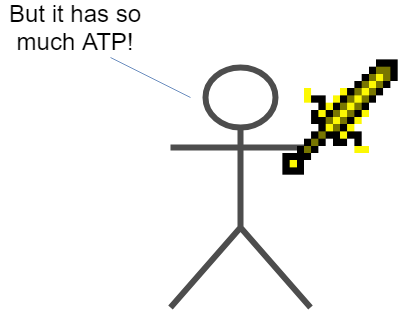

But, whoa! Look at that Tungsten Carbide. Super sword metal right here*!

*of course not, or else we would be using it for swords already.

Toughness

Believe it or not, this is not the same as strength. Think of it as the ability to bend rather than break.

Something can be strong and not tough.

A material that is not tough, in addition to being unable to deal with harsh truths, doesn’t handle the shock of impact very well. And swords… well they tend to hit stuff[citation needed].

Tungsten Carbide does not have toughness. Despite the hard outer shell it presents to the rest of the world, it’s secretly brittle on the inside.

For those of you paying attention to the differential hardening section, you might ask why we can’t use some sort of hybrid between Tungsten Carbide and regular steel. As a matter of fact, this is something that is very common in drill bits. Ever wonder why they tend to be yellow on the outside? That’s a layer of a hard outer metal (Tungsten Carbide or similar material), layered on top of a steel body.

What if you tried this on a sword? A few problems. If the blade ever flexes you are going to experience severe cracking in the outer coating. It’s also going to be impossible to sharpen without wearing the outer coating off. But if a company did such a thing you would get a novelty sword with a cool looking outer coating, which maintained an edge for a very long period of time, didn’t rust, and…

Steel vs Titanium, the Final Showdown

So, while we’ve made a case for not using most other metals instead of steel, the one that hasn’t been wiped out of contention is our modern space age super metal: Titanium.

Titanium has a reputation as an advanced engineering metal, because it really does have a lot of very desirable properties. Specifically it has a very good strength to weight ratio, and is tough. Other than its high cost, there are two things that are preventing it from being a great sword material:

Hardness – Unfortunately, Titanium just can’t get as hard as steel can. It won’t hold an edge as nicely, and a training sword would get chewed up like the low quality feders on the market.

Absolute Strength – Titanium has excellent strength to weight ratio, but it just isn’t as strong as steel. So if you make a sword out of titanium to be as strong as a steel sword, it will be lighter. But it will also be bulkier. And when you are trying to limit your profile, to make cutting through easier, you don’t want bulk.

So, no, despite what cool sci-fi sword you saw on TV, titanium super swords aren’t really something that could be a thing. Rather than thinking of it as a super steel, think of it more as super aluminum. 😉

And of course….

Just about everything I’ve mentioned here didn’t exist at the time historical swords were being made. At that point, steel was the futuristic super metal! And that isn’t to say that modern steels are exactly the same as those found in history. Modern spring steels can achieve really fantastic levels of durability… if subjected to good heat treatment with quality control. Katanas have been made which switch up the Martensite/Pearlite combination with Martensite/Bainite, a steel microstructure only discovered in the 20th century.

But at the end of the day, as the end user, most of it is just marketing hype. Don’t worry about a manufacturer’s claim of super steel. Just look at their track record. 😉