In the previous article we explored the concept of affordances, as described by James Gibson and followed up by researchers the world over. This time we look at another of Gibson’s extremely important ideas, Direct Perception. It is the idea that we don’t actually create a mental model of the world, and the visual information we take in doesn’t need to be “decoded” at all.

This is Part 4 of my series on Ecological Approaches/Psychology. The article stands alone, but is part of a broader modern understanding of human action and perception.

- Part 1: Ecological Psychology

- Part 2: Motor Solutions

- Part 3: Affordances

- Part 4: Direct Perception (you are here)

- Part 5: Perception-Action Coupling

- Part 6: Control Laws

- Part 7: Implications of EA

Tau: Direct Perception of Time to Contact.

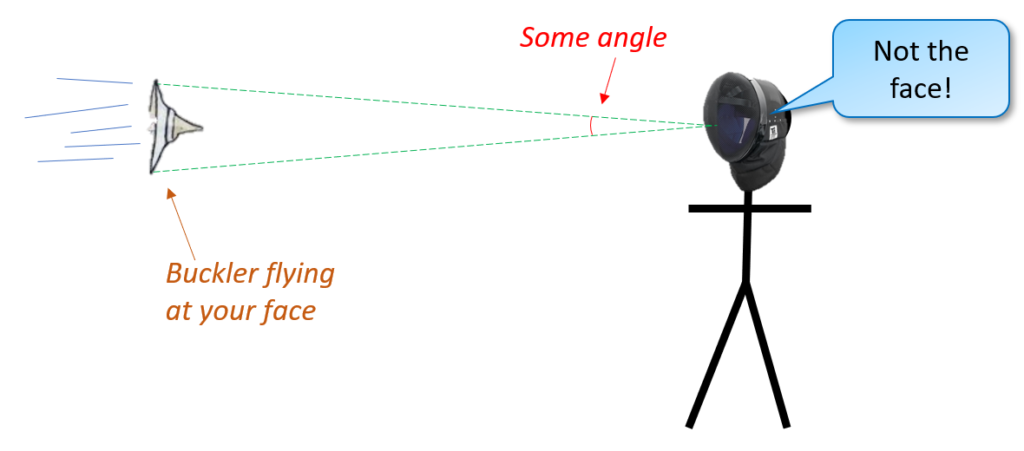

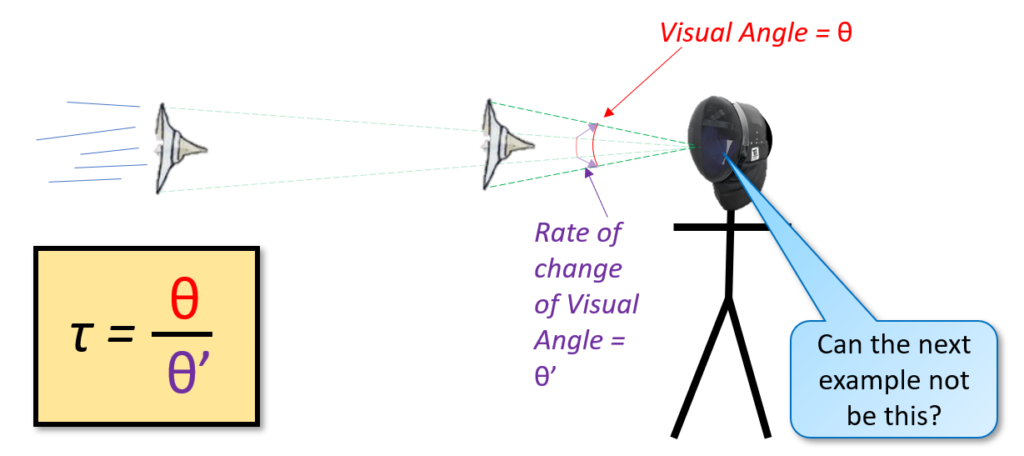

One of the simplest and “cleanest” illustrations of direct perception is in the property of tau to estimate time to impact. Imagine that you were dozing off in the middle of the ring and then all of a sudden you open your eyes to see a buckler flying at your face.

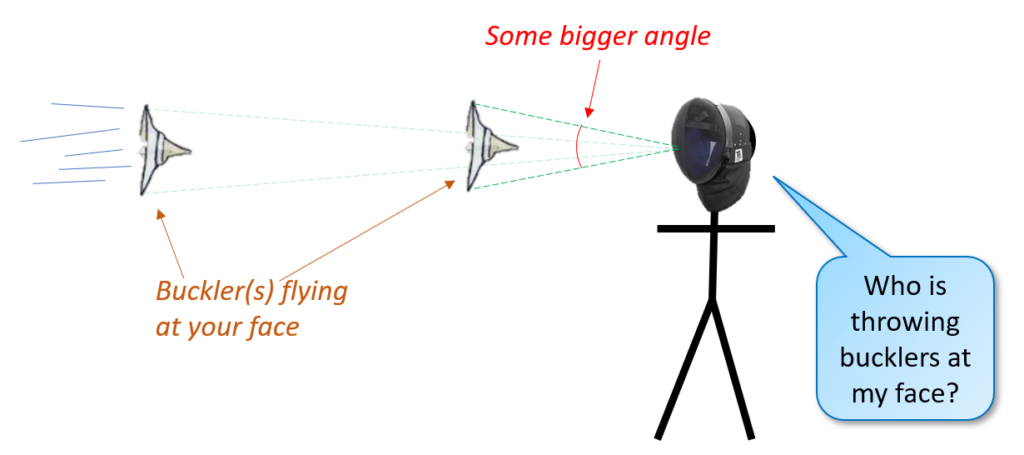

This buckler is going to be taking up some percentage of your visual field. The same object being closer will take up a larger angle, and further away it will take up a smaller angle.

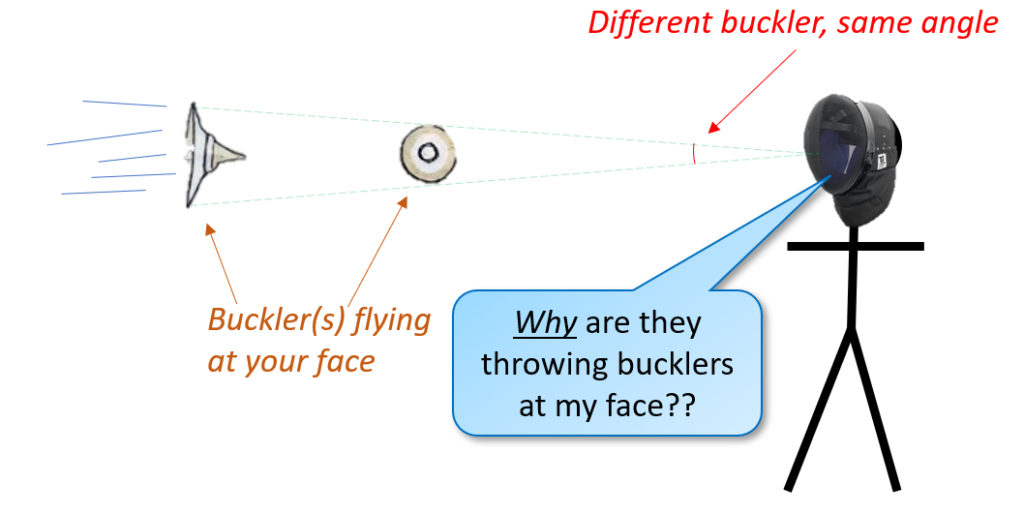

Likewise a smaller buckler closer to the face will take up the same angle as a larger buckler further away.

The rate of change of this angle is known as looming. The larger the looming, the faster something is approaching. Using conventional Information Processing Approaches you would expect that one would take this information, feed it into a mental model which estimates the flight of the object, and how long it takes to make contact (with your face).

However this is completely unnecessary! Let us introduce tau (τ), which is the visual angle divided by the rate of change of the visual angle.

How is this interesting? Because tau is the time-to-contact. You have no need to estimate time to contact, because you have all the information you need being constantly fed to you. The amount of time it takes for something to reach you is already encoded into the information that is constantly flowing into your eyes. And this is true for all time-to-contacts. It doesn’t matter if you’re observing a paper airplane from the bored coworker in the desk next to you, or an asteroid billions of kilometers from earth. The same relationship holds true regardless of size, distance, or speed. No matter if it’s a thrown buckler or an asteroid from space, just by looking at an object we have everything we need to know about how long it will take to reach us – no mental modeling involved.

Higher Order Information

Time-to-contact was just one example of how Direct Perception eliminates the need for sophisticated mental modeling. If we needed to calculate the distance and velocity of an object, the information available from our visual system is in fact quite impoverished, and results in a need for estimation. Which is why humans suck at these estimation tasks, but can still reliably move and interact with their surroundings effortlessly.

Tau is what’s known as Specifying Information: information that has everything required for its use. If you had to calculate time-to-contact from first principles you would need quite a bit of additional information and modeling. One of the most important parts of skill development is attuning the body to specifying information sources rather than non-specifying information sources.

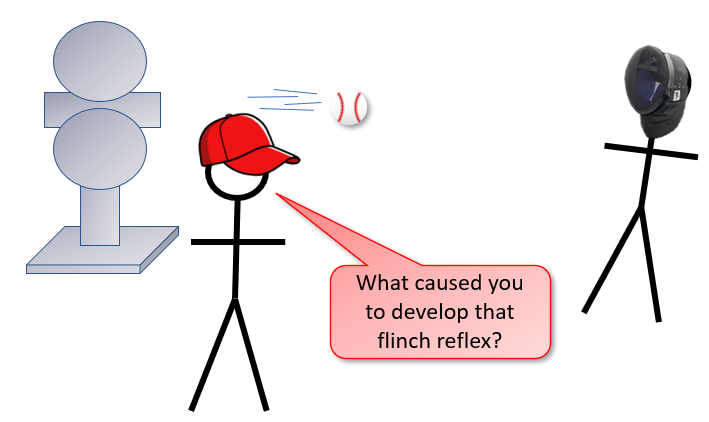

Imagine you are learning to hit a baseball and working with a pitching machine. You might think that it’s important to practice getting the timing right on the constant pitch speed first, and then start working on different speeds. If you read Part 2 you already know that “getting it right” from a technical point of view isn’t something real. This is true from the timing point of view as well.

As the ball approaches you it will appear to grow. The simplest way to time your swing is “when the ball gets <x> big, swing”. Which works for a machine that pitches the same size ball at you the same speed every time. But if you “learn” the timing and then switch to a different speed, everything you just spent your effort practicing goes out the window. All of a sudden you need to learn something new.

Eventually athletes must learn to switch to a tau-based perception, as it’s the only way you can handle real world variability. But all the time invested in repetition of a constant stimulus action is wasted, because the perceptual skills have to be discarded and a new, better, strategy learned. If the practice had instead been variable from the start it probably would have taken longer to get “good” at timing, but the time spent would have been real skill development. What takes longer, getting good at an isolated task quickly and then struggling through re-learning how you perceive and action, or having a slightly slower learning curve practicing a variable task and developing the skills that will be useful all the way through to high level competition? (For more on the difference between apparent vs actual learning, refer back to Block vs Random – When Improvement Isn’t Really Improvement)

I Can Never Escape The Finnish Chicken

It seems that these articles keep coming back to the lessons learned from my struggles with the Finnish Chicken game. (F*ck The Finnish Chicken – A Case Study of CLA Games Implementation, Revenge of the Finnish Chicken). In Part 3 I identified how attuning people’s attention to the affordance of hitting, rather than the distance, had the most success at getting people to attack at the appropriate range. This can also be examined in the context of specifying/non-specifying information.

From my anecdotal observations it appeared as if the fencers always got to the place where it felt “right” to attack, and then attacked. (The non-true-place, if you will.)

However the Finnish Chicken game, by nature of its restrictive and predictable targeting, requires you to be much closer than normal if you want a realistic chance of landing. Which was something that was intellectually understood by the fighters. Yet they continued to engage from out of distance.

This is likely because they were ‘wired’ from previous training in the manner of “this close means it is the time to attack”. Which is why a focus on getting closer didn’t help; the reaction to attack fired as soon as someone crossed the ‘threshold’, so to speak. An affordance, on the other hand, is a source of higher order information and will scale with the constraints of the game. By attuning their attention to the affordance, the pattern could be broken. But could this problem have been avoided in the first place if they hadn’t originally learned in a context that had all attacks coming from a similar distance? Probably.

Cues & Decision Points

In the article Reaction Times in HEMA, Stephen Cheney brings up a very important point: the times involved in our fencing actions are much shorter than our “reaction time”. It states the reason we are able to have success is we don’t wait for some discrete cue, but are constantly acting on information we perceive from our opponents.

I did a motion analysis on the lunge speed and distance of both Rob Childs and Myles Cupp, performed in a controlled video-capture setting. For those of you who aren’t familiar with the names, Myles is a good rapier fighter and Rob is an outstanding rapier fighter. Rob is known for his blazing fast lunges that hit before the opponent can react. Interestingly, the actual analysis showed the opposite, with Myles being able to produce a higher speed and distance of lunge.

So what gives? This is a case of continuous vs non-continuous information. In the experiments, they were both standing stationary in stance, and performed the lunge when they were ready. Which is a completely artificial setup. The results were very conclusive over many different trials. Myles had the faster lunge. Yet in practice it is Rob who is by far the “faster” attack.

This is because a lunge, or any fencing action, is part of a continuous flow of information that each fencer is providing to each other. In the video experiment the clock started when the fighter started to move. In reality the “clock” starts as soon as the defender realizes they are vulnerable. Each fencer provides a continuous flow of visual information to the other, and whatever higher order information that opponents are picking up off of Myles, it is enough to negate any sort of speed advantage he may have in optimal conditions. Which leads into the topic of the next article: Part 5: Perception-Action Coupling.

What Does This Mean?

I’ll wrap up each article with a more concrete example of what implications the concept has for coaching. In regards to Direct Perception the most important takeaway is that you need to have variable and earnest stimulus to learn how to perceive the important information relating to a skill.

Just like the example with the baseball that moves at a fixed speed, if you are getting compliant attacks so you can learn the technique “properly” then you are not learning to pick up on any information relevant to the practice of the skill. Learning how to use the most useful information from your opponent is a fundamental part of the technique and can’t be isolated. Training on a non-resistive opponent trains you to fight a non-resistive opponent, plain and simple. “Boards don’t hit back” and all that.

Stuff for (History) Nerds: Fuhlen

On the subject of strong/weak for KdF practitioners, I also inadvertently uncovered something interesting when looking back at the glosses with an eye to Ecological Psychology. Here is an excerpt from 6 Bad Games – Lessons From The Rondo:

… I went back to the glosses [Ringeck – Danzing – Lew Longsword, Cheney, 2020] to see if there was a reading that could imply that strong/weak is based on continuous perception. And was disappointed to read that it instructed you to feel for weak/strong by using your hands.

But in subsequent conversations with Steve Cheney it looks like this might have more to do with translation than anything. Here are Steve’s words:

In the passage about feeling and indes from the RDL texts, there is a phrase “zu hant” that is often translated as “by hand” or “by the hand,” including in my own book of translations. “Zu hant” literally means “to hand,” and it is understandable to translate it this way, however rather than being literal, it is likely an idiom meaning “immediately.” Grimm’s dictionary has an entry for the word “zuhand” as an adverb meaning “sofort, sogleich,” IE “immediately, right away,” and a sub entry under the “hand” definition for “zu hand” meaning “alsbald,” IE “immediately.”

In all cases of its use in RDL, “zu hant/zehant/zuhand” is treated as an adverb modifying “fühlen.” As a comparison to English, think about the phrase “the time is at hand,” in which “at hand” does not literally have anything to do with your hands. The phrase “zu handen” also exists which could have the sense of taking something by the hand, but none of the examples from RDL take that form, and the use case in the examples given in Grimm seem quite different from what it would be if it were used that way in RDL. Overall, I think all signs point to the meaning of “zu hant” in RDL to be “immediately” or “right away” rather than “by hand.”

So perhaps instead of “go use your hand to sense how hard they are pushing” it’s not so much of a stretch to think in terms of “perceive if they are conducting themselves in a strong or weak manner”.