An important part to understanding how to use Ecological Approaches is the concept of an “affordance”. Many people who have some familiarity with design work might be thinking “I know what that is!”. And in most cases you would be wrong.

This is Part 3 of my series on Ecological Approaches/Psychology. The article stands alone, but is part of a broader modern understanding of human action and perception.

- Part 1: Ecological Psychology

- Part 2: Motor Solutions

- Part 3: Affordances (you are here)

- Part 4: Direct Perception

- Part 5: Perception-Action Coupling

- Part 6: Control Laws

- Part 7: Implications of EA

Enter The Main Actor

This story starts with James Gibson, a researcher who published many highly influential works on human perception in the post-WW2 years. Gibson had served as a researcher in the US Army Air Force during the war, and unlike a certain other famous Air Force pseudo-scientist*, started asking some very useful questions about how we perceive things.

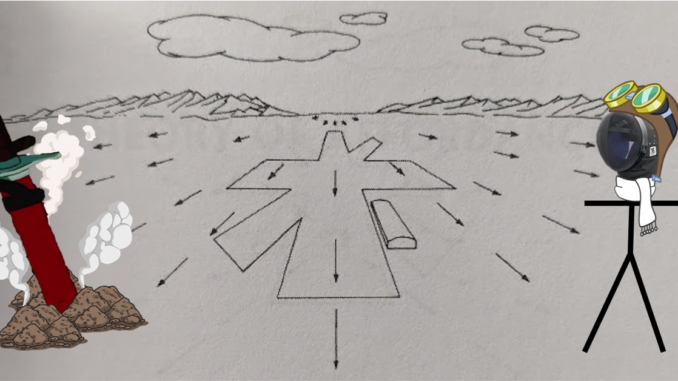

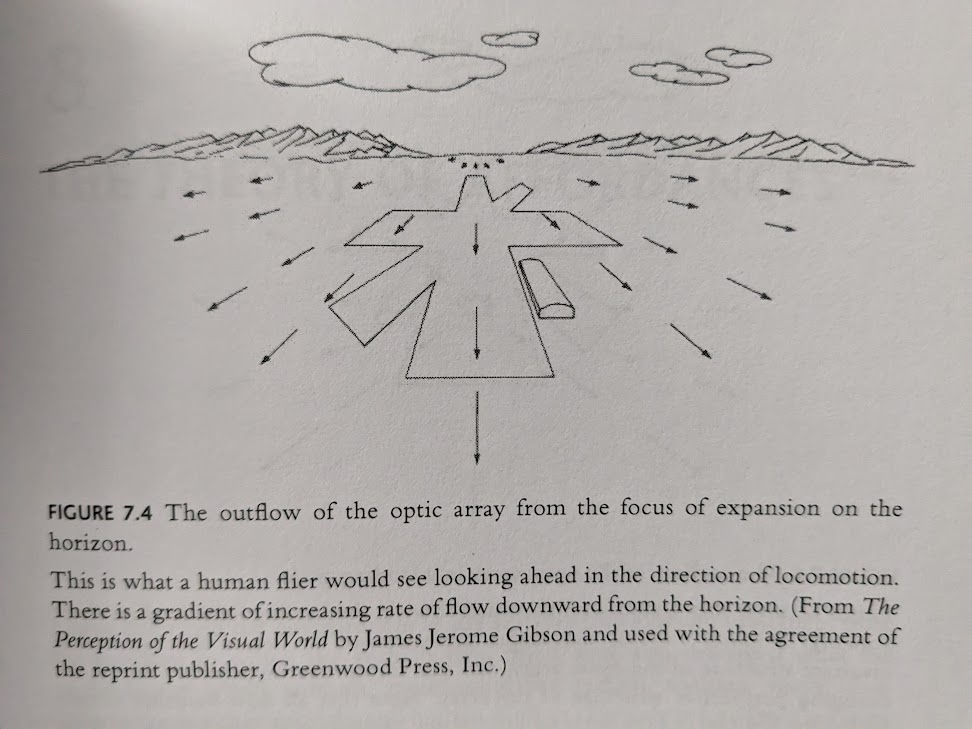

I’ll not go into the depth of exactly how Gibson’s ideas work, because they are super technical when you start breaking down things like Ambient Optic Array, and I don’t think I’m qualified to explain them anyways. What is important to us is Direct Perception and Affordances. If you browse the list of article titles you’ll see that Direct Perception is a topic for next time. So on to Affordances!

*It’s James Boyd. I’m making fun of the OODA loop fanboys.

What Is An Affordance

According to Gibson,

“The affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill. The verb to afford is found in the dictionary, the noun affordance is not. I have made it up. I mean by it something that refers to both the environment and the animal in a way that no existing term does. It implies the complementarity of the animal and the environment.”

So what the heck does that mean? Basically an affordance is what can be done in relation to the environment. A chair offers the affordance of sitting on. A ball offers the affordance of being thrown. But the chair also offers the affordance of being thrown, albeit not nearly as well as the ball does. The ball may also offer the affordance of being sat on depending on size (or tolerance for discomfort? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ ).

If you’ve heard of affordances before, this may sound incorrect. This is because Donald Norman later used the term in the context of design in his highly influential The Design of Everyday Things. For this article we are talking about Gibson and not Norman. If you can’t let go of what you think you know about affordances, then consider that there are g-Type and n-Type Affordances, and we are going to talk about the former.

Norman actually disliked the way that the design community co-opted his use of the term affordances to mean something different than what he originally intended. Norman was a contemporary of Gibson, and the two had frequent interaction. In the later post-digital-age re-release of The Design of Everyday Things he laments:

“Designers needed a word to describe what they were doing, so they chose affordance. What alternative did they have? I decided to provide a better answer: signifiers. Affordances determine what actions are possible. Signifiers communicate where the action should take place. We need both.”

But we are here to talk about swords hitting faces, and not the ins, outs, and history of terminology associated with smartphone design.

What Is An Affordance, Actually

Let’s start with an example: have a look at this staircase from the Royal Armouries in Leeds and estimate how tall each step is.

Studies have shown that people basically suck at this task. Unless you’ve specifically spent time training yourself to estimate the size of small vertical surfaces (and we thought HEMA was a niche hobby) you’re unlikely to get especially close. People are all over the map, over and under with no consistent pattern.

Something interesting happens if you ask people “can you walk up this comfortably without it disrupting your stride?”. All of a sudden they get extremely good at knowing the answer to your question. Which seems odd, as this is a question without an absolute answer. Taller individuals are able to use taller steps without disruption, and people who are fatigued are only able to maintain stride over smaller steps. Regardless, the answer is consistently accurate for their current physical condition.

Affordance vs Modeling

Using a conventional theory of perception, the above situation doesn’t make any sense. According to the IPA model we go through the following steps:

- Take in information from senses.

- Make/update our model of the world.

- Decide what skill to execute based on this model.

- Send out motor commands based on a template of how to execute the skill.

Clearly we can see we absolutely CAN’T be making a model of the steps because we have no freaking clue how tall they are! But the results hold up time after time, no matter which way we try to investigate how humans perceive the world.

Needless to say, this upended what was assumed to be the process of human understanding and action. Though this was revolutionary, the implications are still not particularly understood or implemented in most fields to this day.

As you can see, this isn’t exactly radical and new knowledge, it’s just knowledge that hasn’t been widely adopted. Gibson started advancing these ideas in the 1950s. And Nikolai Bernstein, the other ‘founding father’ of Ecological Psychology we discussed in the last article, was publishing in the 1920s.

Affordance vs Action Capacity

Before I move on to the last topic (why you should actually care about this “affordances” thing), we should clear up the idea of an Affordance vs that of an Action Capacity. An affordance is always relative to the person perceiving. Currently the kitchen counter offers you the affordance of putting something down onto it, and conversely something on the kitchen counter offers you the affordance of being picked up.

But to a small child the counter does not offer these same affordances, because they cannot reach the counter. This doesn’t mean that the counter is inaccessible. The drawer handles may offer the child the affordance of climbing to the counter, in a way they wouldn’t offer an adult (who weighs considerably more).

The Action Capacity will govern what is and isn’t an Affordance. In an example with switching baseball bat weight, they found that some individuals experienced far higher negative performance impacts than others. Upon investigation they found that some batters had to compensate for the slower bat speed by swinging earlier, which led to lower accuracy. Others who had higher strength were able to compensate by swinging harder, leading to higher accuracy because they had more time to perceive information leading up to their swing.In other words, they had the action capacity which offered the affordance of swinging the bat at a higher speed. (Note that these adaptations were not conscious for either group.)

In a more personal example of Action Capacity affecting Affordances, we can look at the real world example of my reduced hip mobility. I have almost no ability to do internal rotation in my hip. To get a feel of what that is like, sit down on something high enough that your feet aren’t touching the floor. Now, while keeping your upper leg pointed forward, rotate the feet out away from each other. On a normal person you’ll probably get around 30 to 45 degrees of rotation. I have about 5.

This is very relevant when I’m grappling, as if you’re trying to get out from underneath someone one of the most common maneuvers is the “shrimp”. Which I won’t get into technical details on, but is hard to do effectively enough vs an earnestly resisting opponent if your hip is locked in place. Thus I do not have the Action Capacity to execute this technique and thus the strategies for getting out are significantly impinged.

BUT, the story isn’t over. I’m also quite physically strong (or was, until I stopped training) and I’m able to push someone hard enough away from me that I can practically throw someone of comparable body weight directly off if they let me get my arms between us. In this sense I have an Action Capacity that most other people lack, and thus what appears like a good approach to deal with the situation is going to look very different to me than to most other people in the same situation.

Use of Affordances In Training: Cues

In the past you may have enjoyed me floundering around trying to instruct people who are playing the Finnish Chicken game. (F*ck The Finnish Chicken – A Case Study of CLA Games Implementation, Revenge of the Finnish Chicken). The TL;DR was that everyone understood they were attacking from too far away, but somehow the instructions to “get closer” never seemed to help. This was before I was well versed in the concept of affordances, and I was ripping my hair out trying different ways to get people to attack at the proper distance. (And I don’t have that much extra hair to spare nowadays.)

In the end the only thing I ever said that seemed to have any positive impact was “don’t attack unless you’re very confident you can actually hit”. This succeeded where “get closer” failed, even though “get closer” seems to be far more concrete and actionable. And guess what, it’s an affordance.

In fact, the concept of “measure” itself is almost the textbook definition of affordances hiding in plain sight. We all know that we don’t use the generic term “distance” because there are more things that go into hitting someone than the physical separation between the two. But when giving people a correction the language immediately devolves back to concepts of absolute measurement. “Get closer”, “watch your distance”. Things which humans are terrible at understanding and acting on.

Use of Affordances In Training: Practice Design

Getting into the habit of using affordances when giving instructions is one way you can help your students use feedback more effectively. (Though this means saying “pay constant attention to if they can just reach out and hit you” vs “don’t get so close”, not having an in-depth discussion about the differences between g-Type and n-Type affordance terminology.) The greater utility is using the knowledge in how we design our training activities. We want people to be able to perceive and act on the best affordances they have available, rather than doing arbitrary techniques in vacuums. But how exactly are they even seeing these affordances in the first place?

Which is a nice segue into the next article in the series: Part 4: Direct Perception. Bye!

What Does This Mean?

I’ll wrap up each article with a more concrete example of what implications the concept has for coaching. In regards to Affordances the most important takeaway is to design your constraints such that the activity affords the successful employment of the skill and does not afford the unsuccessful employment of the skill.

If you want students to learn to do a dupliren, create a scenario where they would want to work on the same side of the blade, rather than cutting around. The key is they have to want to do it. If you are doing a training activity where the only thing stopping them from cutting around is the fact you won’t let them, then they aren’t really learning about what situations afford the dupliren vs a zwercopter.

The Can Opener game is a good example of this, as the constraints have made doing a dupliren relatively more attractive option, but it is ultimately not mandated and won’t be forced if it isn’t a good idea. Affixing weights to the right wrist will make the dupliren an even better option, as it only requires engagement of the unweighted off-hand.

Stuff For Nerds: Affordances & Penguins

Apparently once you start seeing the world in terms of affordances you just can’t stop. Take for example the pinnacle of high-technology military development: the brand new F-35 fighter jet.

Rather than talking about Top Gun-esque stuff like dog fighting, what all the military aviation reports seem to be gushing about is the concept of Sensor Fusion. Which is a lot of things, but one of the features that is signaled as being remarkable is that the traditional instrumentation has been completely gutted. Instead of having a number of different readouts for the multitude of different radar/infrared/whatever systems the aircraft possesses, it has a display which synthesizes the inputs from all of them and displays an overall picture of the tactical space with priority to what is most relevant at the moment.

That’s right, the biggest innovation for the latest stealth aircraft is the fact that it now no longer feeds a pilot raw data, but affordances. 😊