As I was writing an article for Game Design 4 HEMA I went to grab a link to the SwordSTEM article on Internal vs External Cues and found that… it somehow doesn’t exist? External focus of attention is the first thread that I ever pulled on from the whole Ecological Psychology ball of yarn, and somehow I never wrote about it. (Despite referencing the idea numerous times.) So here we are, to the article I’m sure everyone has been waiting for with bated breath.

The improved effectiveness of external vs internal focus of attention has been shown in many, many, many studies over and above the two from Wulf that I use as examples in this article. To quote paraphrase Rob Gray “I really wish people would stop doing so many of these internal vs external studies, because it always shows external being better and we could be looking into so many more interesting topics instead”.

What Is Internal/External?

The two types of focus are:

- Internal: Focusing inside the body, such as “move my hand forward”.

- External: Focus outside the body, such as “tag this object”.

This can be subdivided further, with the external focus being either near or far. Driving down the road and focusing on the position of the hands to steer the car would be internal. Focusing on the angle of the steering wheel would be near external focus. Focusing down the road to keep the car going straight would be a far external focus.

You will notice that I seem to be switching between “cue” and “focus of attention” as if they are interchangeable. There is a slight difference in that the focus of attention is where someone is concentrating while doing a skill, whereas the cue is an instruction on where to concentrate while doing the skill. Which is close enough to the same thing that I will continue to use them interchangeably lest I get bored of one.

The Stupid Experiment That Wasn’t Stupid

The classic external focus experiment is one performed by Gabriele Wulf in 2003. Participants were placed on a balance board, with the goal of keeping it as level as possible. The difference was in the instructions they were given to accomplish this task.

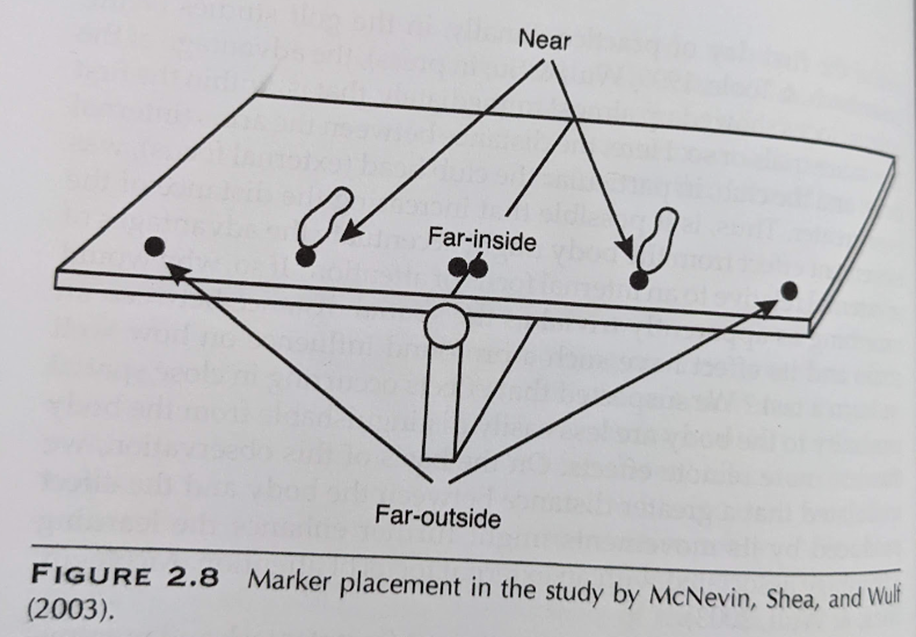

There were 4 groups:

- Internal: Instructed to keep their feet level.

- External Near: Dots were marked just in front of their feet, which they were told to keep level.

- External Far-Insider: Dots were marked near the center, which they were told to keep level.

- External Far-Outsider: Dots were marked at the far outside, which they were told to keep level.

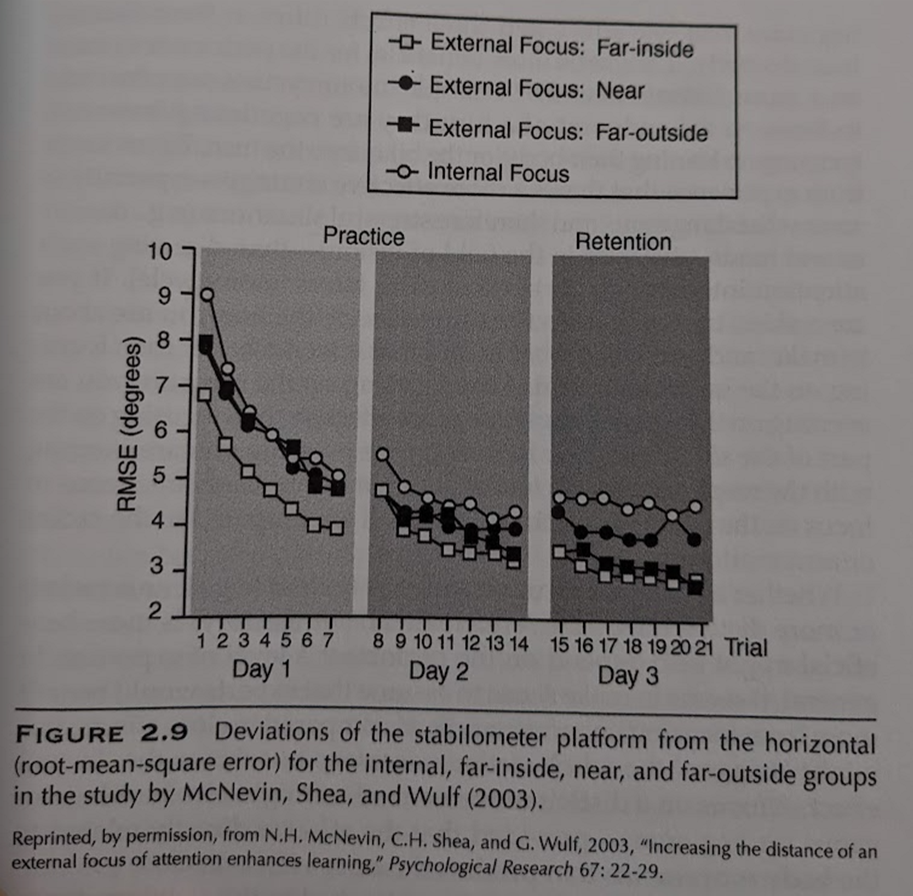

Results were recorded, and the root-mean-squared error was calculated. (Don’t worry if you don’t know what that means, bottom line is the lower you are the better you are at keeping stable.)

The results show that focusing on a dot just in front of your foot is better than focusing on your foot. Which is crazy!

This study was designed to investigate the effects of near vs far external focus, and the internal was the control group. I like to use it as an example because it gives an external focus which is almost internal, yet an effect is still noticeable.

External and Frequency Response

So how does this external focus of attention black magic work? It starts with the idea of a Motor Solution, the idea that any task is extremely complicated, has no exact “correct” muscle activation pattern, and requires many muscles working in harmony throughout the body (Part 2: Motor Solutions – Introduction To Ecological Approaches For Coaching).

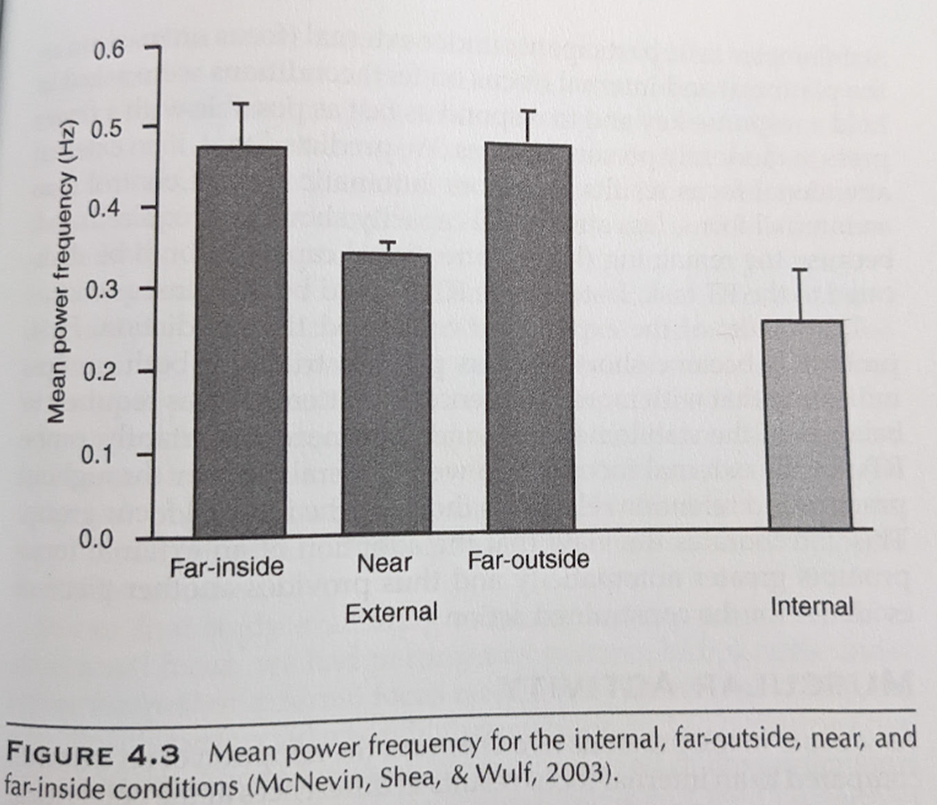

The following data is gathered from the external distance of focus experiment described in the previous section. It is a measure of the frequency of the “wobbles” on the balance stand. More frequency = less time between, so the higher the bar the more corrections per second there are.

We see a pretty strong correlation between performance and high frequency of balance corrections (from Figure 2.9). Which means that the reason for the improved balance is that the body is faster at self-correcting when we just get the [heck/hell] out of our own way. You can think of your conscious focus as the annoying manager coming into the department to micro-manage, and messing everything up in the process.

Moral of the story: if you want to balance, focus on keeping something external to your body level, and not your body itself.

External and Distance Of Focus

The experiment by Wulf in the previous section is a great example because it showcases not only the superiority of external cues, but because it shows the effect of distance of focus. An external focus always beats an internal one, and getting the external focus away from the body is better than keeping it close.

For example:

- Telling someone to drive their point to the opponent is better than;

- Telling someone to push with their pommel, which is better than;

- Telling someone what to do with their hands.

While this is true, it somewhat suffers from diminishing returns. Keeping the focus on the overall goal is the best way to go, rather than being dogmatic about keeping the cue as far out as possible. Usually there are only one or two viable options for cues, and stressing out about distance just over complicates the situation. In my opinion, it’s probably better to just focus on using external cues over internal cues. That is a hard enough transition in terms of instructional style.

External and Learning Retention

The evidence shows that keeping an external focus of attention makes us do the skill better. But is that sufficient to show that we learn the skill better? We know that some approaches produce an immediate improvement in skill but lack in long term skill retention (Block vs Random – When Improvement Isn’t Really Improvement). How does external focus stack up?

For an example, let’s look at a different study by Wulf. In this participants were asked to hold a hollow tube horizontal while standing on a balance board.

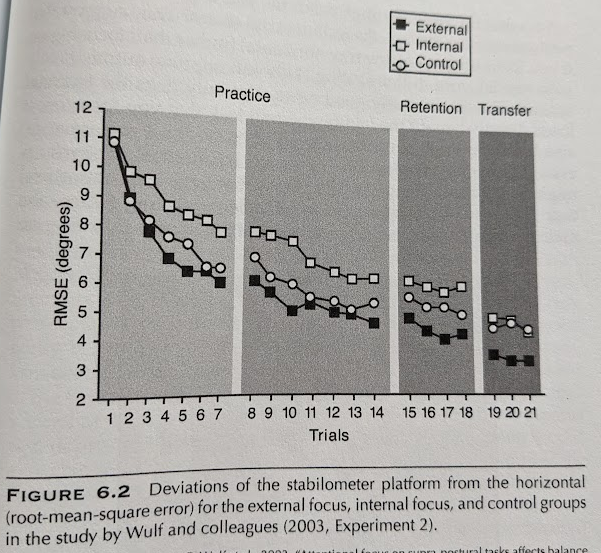

There were three groups this time:

- External: Told to keep the tube horizontal.

- Internal: Told to keep their hands horizontal.

- Control: Told to keep balanced on the board, no instructions relating to the tube.

This study had both a retention and transfer test. The retention test was their ability to perform the task after a break between training and testing. The transfer test was their ability to balance on the platform without balancing the tube.

The following are the platform stability scores from the experiment, and – like before – lower is better. (Note that until the transfer test, neither the external or internal group had platform stability as an explicit goal.)

This shows that even though the external group was focusing on holding the tube level, they were also doing slightly better at keeping the board level than the group that was focusing on… keeping the board level. And what was really interesting was that after the training was complete the group that had trained to keep the board level was the worst at keeping the board level.

The implications of this are that if you want to increase your balance in fencing, you’re going to learn balance faster doing sword skills while in positions of instability rather than actually training to be balanced. (Not that “balance” was ever a discrete learnable skill to begin with. Dynamic vs Static: A Generic ‘+Balance’ Stat Doesn’t Exist.)

Implications

This means that when you are giving someone something to focus on, you should be trying to give them an external cue. For instance, if you are having people doing an action and you notice a flaw you want to correct, it is better to give them a target to be reaching for with their blades than to tell them something like “hands higher”.

Here are some examples of internal vs external cues you could use:

| Internal | External |

| “Extend your arms to cut.” | “Drive the point towards your opponent as you cut.” |

| “Make sure you keep your arms straight out from your shoulders.” | “Keep the sword’s crossguard in the center of your chest.” |

| “Move your off-hand forward towards their shoulder.” | “Imagine they are a pirate and you want to punch the bird sitting on their shoulder.” |

| “Feel how hard they are pushing on your blade.” | “Feel if they are pushing their point across your body or not.” |

| “Rotate around your right hand.” | “Reach for the ice cream while you are rolling the sword around.” |

With all that said, coaching via direct instruction is still not as effective as methods such as Constraints Lead Approaches (CLA). This is when a constraint is given, and the student explores all the possible ways they can achieve success. So while giving direct instructions and form corrections is not necessarily the best way to train, it is what most people are doing. Framing these instructions in terms of external cues will help get the most out of it.

For more information on CLA, and other Ecological Approaches to Coaching: Part 7: Implications of EA – Introduction To Ecological Approaches For Coaching.

Stuff For Nerds

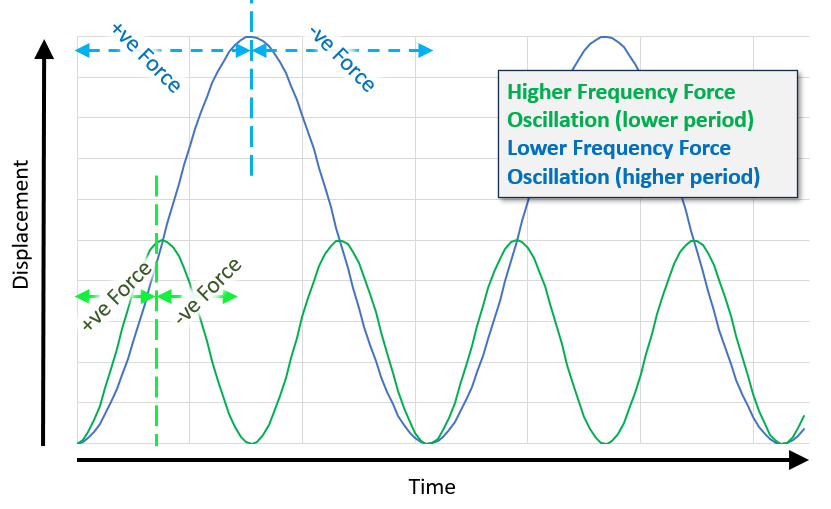

In the part about frequency response I kind of glossed over why having a higher frequency response is better. That is because the details, while super interesting to me, are also not really necessary to understand from a coaching point of view.

You can think of frequency in terms of “how often are corrections made”. For example, imagine you are driving down a road with your eyes closed and only get to have a quick blink of eyes-open every 1 second. You’d probably not do too bad, so long as you’re not going too quickly and the road isn’t too unpredictable. But as you start to increase the period to 2, 3, or more seconds between opening your eyes you will see bigger swerves back and forth while trying to keep the car in the lane. And eventually at some point you’ll lose the ability to keep on the road at all.

The below shows two hypothetical objects which have an alternating force on them, with the high frequency force switching direction twice as fast as the low frequency force.

As you can see, the lower frequency leads to much bigger displacement. If this was a physical system it means that the wobbles* would be much bigger than the wobbles of the higher frequency of force corrections.

*totally a proper technical term. Drop it into your next conversation with an engineer to impress them.