In the year 2000 Antoinette Gentile published a framework of understanding and classifying motions based on four controlling dimensions. This framework, which has come to be called the Gentile Taxonomy*, can be useful in helping to classify different actions and what are the prime challenges to overcome in accomplishing them. In addition it is meant to draw attention to the dynamic nature of many tasks. In the words of Gentile herself:

“If the task involves objects and people that don’t vary, then you can set practice that way, but if a task involves motion in the environment and that motion necessarily changes from trial to trial, then practice has to be structured differently. They used to start by teaching the ‘perfect movement,’ with students practicing a swing with no ball and no racquet. The problem was when you got in a game, you had one swing and the task required that you generate 25,000 different patterns, each one uniquely organized to fit the diverse environmental conditions. So my story to the physical educators was, ‘You have to put them in an open environment right from the start.’”

*Antoinette Gentile was a leader in kinesiology and neuromotor research who taught at Columbia University for 44 years. The Gentile Taxonomy appears in many textbooks about human motion and motor control, but the original paper seems almost impossible to find online. Strangely enough, Wikipedia has nothing regarding her or her work. (Someone should fix that.)

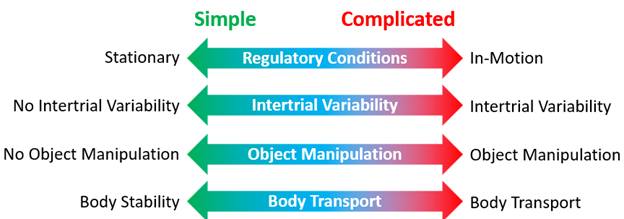

Regulatory Conditions

The regulatory conditions are a product of the external environment in which you are performing the skill. If you are instructed to get from Point A to Point B, it will be a very different task depending if there is a sidewalk or an obstacle course linking them. If you are instructed to cut a target you will approach if differently if given a messer or a rapier.

In broad strokes Gentile categorized the Regulatory Condition as Stationary or In-Motion. Colloquially speaking ‘in-motion’ tends to allude to the physical location of objects, however it actually refers to the whole package of time and space. Tasks which are performed in response to stimuli are also In-Motion skills, even if the distances between all elements are fixed.

| Stationary | In-Motion |

| Performing lunges against a target. | Performing a lunge the exact moment your opponent steps into measure. |

| Cutting a tatami mat when you are ready. | Cutting a tatami mat when prompted by an external signal.. |

Intertrial Variability

Is it the same thing every time, or does it change? This can be a big or small change. When doing flowdrills in the air there is no Intertrial Variability; you can do the exact same thing every time. However when cutting tatami there is! With every cut you make the target gets lower, representing a difference on each cut, for which the body must compensate.

| No Variability | Intertrial Variability |

| Performing a hanging parry against a vertical cut. | Performing a hanging parry against a descending cut of arbitrary angle. |

| Performing footwork in lines back and forth across the floor. | Performing footwork relative to a changing target, or altering your starting conditions. |

Body Transport

Body Transport is, intuitively enough, if you are locomoting your body. It is much easier to drink from a cup of water when you are standing still than when you are jogging (try it!). Which is why the two directions are known as Body Stability and Body Transport.

| Body Stability | Body Transport |

| Lining up and planting your feet in front of a tatami mat before cutting. | Chasing a tatami robot around the floor while cutting. (It’s so much fun!) |

| Standing and waiting for your opponent to throw a strike for you to parry. | Moving around and maintaining distance while being ready to perform your parry. |

Object Manipulation

Are you doing something with an external tool? In most cases we will be performing skills that involve Object Manipulation, the object being our weapon. Note that in this case anything you are interacting with is an object. If you are wrestling you are also performing an object manipulation skill, the object being your opponent.

| No Object Manipulation | Object Manipulation |

| Miming sword motions as you read a manuscript on the bus, while everyone looks at you as though you are crazy.

(Hypothetically) |

Performing a cutting sequence with your sword in hand. |

| Being thrown and performing a breakfall. (You don’t manipulate any objects. The opponent and the floor are part of the Regulatory Conditions). | Throwing an opponent. |

Note: You can also consider how much Object Manipulation is going on. For instance if you are just moving your sword you are doing less Object Manipulation than if your sword is impacting the opponent’s sword. As at that point you are then manipulating two objects.

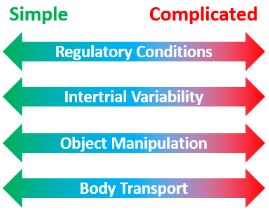

Degree of Difficulty

Naturally each of these dimensions corresponds to an increase or decrease in the level of complication. And the more complicated an action the more difficult it is to accomplish.

In HEMA we tend to hang out to the far right of this diagram. The actions required tend to be complicated, and very demanding.

Regulatory Conditions – You may think that HEMA is constantly “In-Motion,” however it could be worse. The physical environment is just about always Stationary; fighting in an ever-changing arena would certainly ratchet the complexity up to the next level.

Intertrial Variability – Very high Intertrial Variability. If your opponent is good they will keep this as high as possible. The hallmark of a good fighter is to identify patterns in their opponents movements, decreasing the variability and reducing the complexity of the skills required.

Object Manipulation – Not only do we have to manipulate objects, but the objects have a high degree of freedom. In a sport like rowing the oar is affixed to the boat and can only move in so many ways, making the sport intrinsically simpler than a sport like kayaking where the paddle is not affixed and can freely move in all directions. (Some, like me, would therefore label rowing as the lesser of the two. :p )

As an interesting footnote to this topic, modern long-term athlete development models tend to prescribe that young children start in sports which don’t feature object manipulation, and then branch out into object manipulation sports after they have acquired fundamental movement skills and have more maturity in their nervous systems. Which lines up quite nicely to historical practices of starting children wrestling at a young age and introducing swordplay as they grew older.

Body Stability – In general HEMA demands a high degree of Body Transport. However we can sometimes circumvent this a little bit. Ever notice how fighters tend to plant their feet when doing the final adjustments prior to launching an attack? This is a way of increasing their control of a motion by increasing their body Stability, an act which allows them to execute their skills with a higher degree of precision.

Training Progression

How does knowledge of the Gentile Taxonomy help? The advantage is that it allows us to break down the elements of a task and determine if our training regimen is adequately preparing individuals to meet these demands. Which sounds technical, but you are already doing it. What is a training drill, other than a reduction of Intertrial Variability by giving the same input stimulus every time?

If you are having trouble performing a skill, have a look at it from the Gentile Taxonomy point of view (with sparring video if possible). In which of the four dimensions are you having difficulty? When training you should modify the activity to reduce the demands of that dimension so the skill can be acquired, and introduce separate training to help build up the deficient skill. If you are having trouble applying a skill in sparring you can identify the dimension that is lacking, and construct training drills which emphasize development in those areas.

“The Model is Always Wrong”

I had an engineering instructor who had a great saying: “The Model is Always Wrong” (as you probably guessed from the section title). What this means is that any time you try to represent reality with some mental model, such as the Gentile Taxonomy, it will never match perfectly. You will always be able to find flaws. The second part of the quote was “But the question is, is the model useful?”. While we can never get a model that is completely correct, all we need to know is if it is a tool that is capable of helping with the task at hand. Use it when it is, ignore it when it isn’t. And hopefully in reading this you have gained one more tool for your training and coaching toolbox.

Bibliography

Gentile AM. Skill acquisition: action, movement, and neuromotor processes. Movement Science: Foundations for Physical Therapy in Rehabilitation. Carr JH, Shepherd RB. 2000.

Magil R., Anderson D., Motor Learning and Control – Concepts and Applications (11th).

Andrew M. Gordon, Lori Quinn, Terry R. Kaminski & Richard A. Magill (2016) In Memoriam: Antoinette M. Gentile (1936 – 2016), Journal of Motor Behavior, 48:6, 479-481, DOI: 10.1080/00222895.2016.1198193