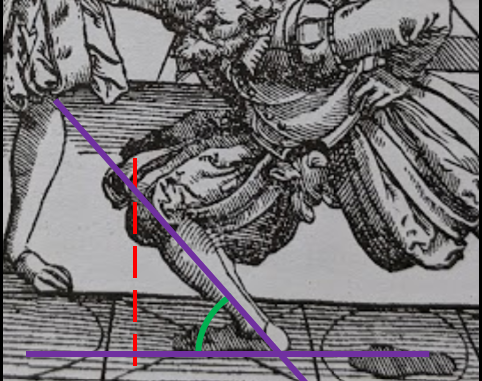

A common piece of advice you may have heard is to never let your knee move forward beyond the front of your foot. I have heard this many times in the context of describing HEMA footwork published in manuscripts, with people writing it off as an “exaggeration”. (For the record, I do think most of the Meyer drawings are exaggerations. But not the parts about the knees)

But the adage about the knees over the toes isn’t true! It is a modern fitness myth.

As far as I can tell this originated from a 1978 paper Kinetics of the Parallel Squat [1] — though I can’t verify this due to academic paywalls. The study found that by moving the knee forward the amount of pressure on the knee was increased. Which is not something good.

Factor in that moving the knee to this range is a large motion. If you are a physiotherapist and are treating a sedentary adult they will likely hurt themselves if you ask them to do any sort of deep movement. I’m assuming that the myth was born somewhere between these two ideas.

But we do it all the time

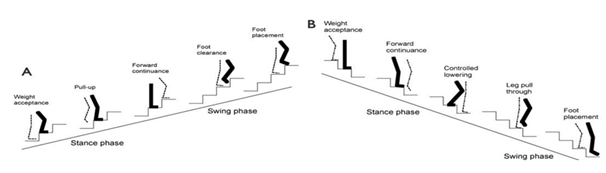

Next time you are on a staircase, take a look down and see what your knees are doing. You will notice that you put your knee over your toes with every step!

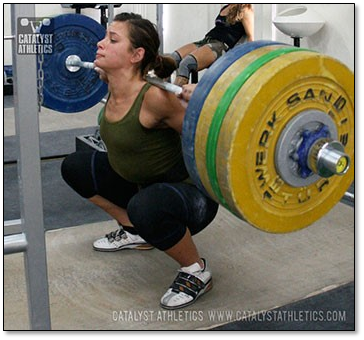

Olympic powerlifters squat with their knees over their toes all the time. And with incredible loads. This should tell us right away that something fishy is up with the “never put the knees over the toes” dogma.

Scientific Testing

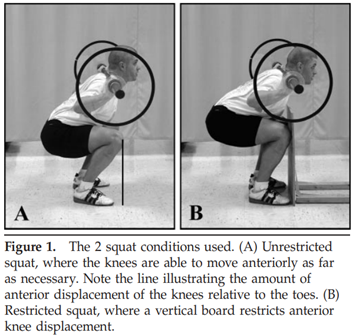

In 2003 a team at the University of Memphis tackled this problem to see if moving the toes forward increased the stress on the knees [3].

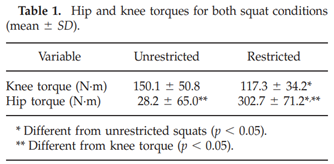

What they found that by allowing the knees to move forward they increased the torque on the knee by 28%. But at the same time by restricting the knee they increased the torque on the hip by 1,000%! Granted the huge percentage increase was based on the fact the hip doesn’t experience much torque in an unrestricted squat, but you can see that the total torque on the body is far higher when the knee is restricted.

In 2013 a study compared results from at 164 published articles on the deep squat[4] and found that:

-

- The highest forces and stresses on the knee actually happen at 90°, not in the deep position.

- “Contrary to commonly voiced concern, deep squats do not contribute [sic] increased risk of injury to passive tissues.”

I have also found several references suggesting that the main injury factor is not how far the knees have gone forward, but where the weight is located on the foot. This means that when the weight is on the heel the knee position is not especially important. But if moving the knee forward results in the body’s weight resting on the ball of the foot, it contributes to increased stress in the knee. This matches what I was taught, and all of my experiences. However I don’t have a research source to back it up. So believe me or don’t!

And HEMA?

The first thing we must understand about any motion is that it must be controlled. This is true of the knee, elbow, or any other joint you can think of. You should be using your musculature to control the motion about a joint, not letting it slam into the end of it’s range of motion. So if you lunge and just allow the tension in the knee to stop your forward momentum, you have problems which are completely unrelated to having your knees ahead of your toes. The knee being forward is a symptom of the problem, rather than the cause.

We also have to consider if someone is able to perform such a position safely, as an individual. While it is perfectly physiologically possible to perform deep lunging motions, it doesn’t mean the average person who walks in off the street should attempt to. Years of not stressing the patellar tendon through this range likely means that they need some work before they can effectively move through this position. On top of this, many individuals lack the mobility in the ankle to perform a deep lunge.

Rather than focusing on the position of the knee ahead of the toes,the focus should be on good solid lunging mechanics. Is the weight of the body under control, or is the forward momentum lurching to a halt when it hits the limit of the range of motion? Or even better, pay attention to how far the knee collapses across the body line.

Bottom line

- There is nothing inherently unsafe with moving your knee over the front of your foot.

- If you’re a coach, don’t have your people do it all at once; if you’re a student, take it a step at a time*.

*literally

Bibliography

[1] McLaughlin, Lardner, Dillman; “Kinetics of the Parallel Squat”

[2] Wahrmund, Jafari; “Motor modeling and optimization of a back actuated lower extremity exoskeleton for stair gait cycles”

[3] Fry, Smith, Schilling; “Effect of Knee Position on Hip and Knee Torques During the Barbell Squat”

[4] Hartmann, Wirth, Klusemann; “Analysis of the load on the knee joint and vertebral column with changes in squatting depth and weight load”