What can go wrong with HEMA Ratings? I mean, outside of the death spiral of sportification it’s encouraging. 😉

People who work with data like to use a saying “GIGO”. Garbage In, Garbage Out. It means that the results you produce are only as good as the information you take in. In our case we aren’t referring to people submitting poorly formatted tournament data (the HEMA Ratings team works very hard to stay on top of this), but data that can paint inaccurate pictures of what is going on.

There are systemic problems which can cause inaccuracy in ratings, even if the information is detailed and faithful. And it’s not like the HEMA Ratings team doesn’t know about them. If you want to do something you have to accept the limitations of what you are doing, after all the perfect is the enemy of the done.

Island Effect

When I said that the organizers of HEMA Ratings know about them, I wasn’t kidding. There is a description of the Island Effect right up on the HEMA Ratings website. But you can stay here, because I’m going to explain it with funny pictures.

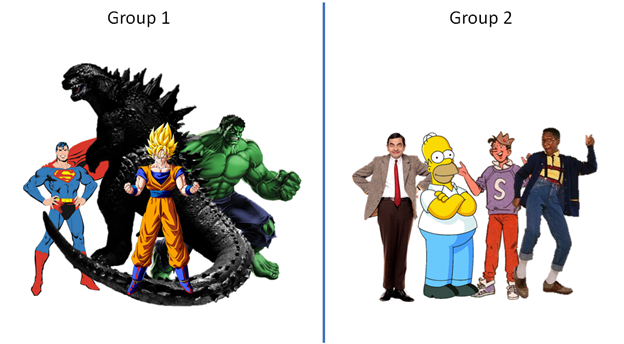

Let’s say you assign two groups of people, and have each group fight within itself to determine the top dog.

After the epic showdown concludes, we have a rating for each fighter. And it would show that the winner of Group 1 was just as good as the winner of Group 2!

This is the “Island Effect”. If the people from Group 1 just keep fighting amongst themselves, and the people from Group 2 fight amongst themselves, comparing ratings between the two will be meaningless. If however, the Group 2 winner visits Group 1 they will get utterly destroyed by everyone. This boosts everyone from Group 1 up, and lowers the rating of the fighter from Group 2. And this Group 2 fighter will in turn spread this to the rest of Group 2 when they return. As long as there is cross over of fighters between groups the ratings can eventually equalize to represent the ability difference accurately when comparing the two groups.

So when looking at a result you alway have to take it with a grain of salt, depending on the size of the island someone comes from.

Number of Exchanges

Imagine we have two fencers named Bert and Ernie, who show up to a tournament. Because he is a much more fastidious student Bert is a much better fencer, and if they fight will Burt will hit Ernie twice as many times as Ernie hits Burt.

Because the tournament organizer (Oscar) forgot to publicize it they are the only two to show up! No problem, Bert and Ernie just get to fight each other ten times and call it a day.

The tournament format is simple, they fight nine scoring exchanges and whoever gets the first clean hit gets a point (doubles are ignored and not penalized).

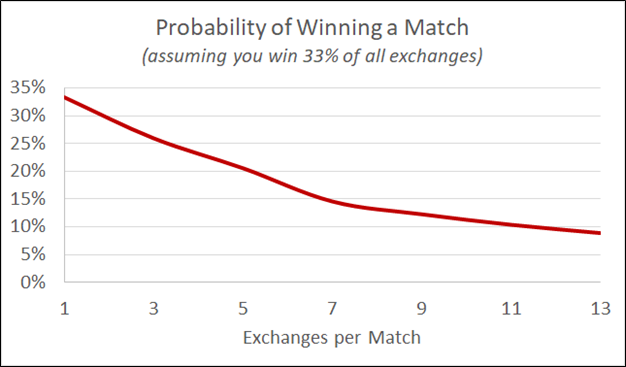

Given what we said about Bert’s skill advantage we can expect Bert to win 67% of the exchanges and Ernie to win 33%. And knowing that Ernie will win 33% of all exchanges we can expect him to win a healthy 12% of his matches. (If you aren’t a math person you just have to trust me.)

This probably seems a bit weird. But let’s think about it another way. What does your average match look like? Bert hits Ernie six times, and Ernie hits Bert three times. But when you zoom out at the match level all we see is that Bert won and Ernie lost. By consolidating multiple exchanges in a match we make the skill difference magnified.

All sports do this, and for good reason. The goal is to create an environment where luck plays a smaller factor, and more skilled competitors can always rise to the top of the field. Aggregating the results (multiple exchanges, multiple attempts, playoff series, etc) are all methods of smoothing out randomness and giving more skilled competitors a disproportionately large probability of winning.

If everyone plays by these rules then it doesn’t really matter, it all balances out. But what if not everyone does?

Let’s say Oscar holds a second tournament. It is equally well attended, but this time Bert and Ernie’s identical twins show up, Bert2 and Ernie2. They are completely identical to their counterparts in skill. The only difference is that Oscar now wants to do a single hit tournament, and since there’s only the two of them they get to fight a whopping 90 matches.

After the results go to HEMA Ratings, what do we see? Bert has a win percentage of 88% and Bert2 has a win percentage of 67%. FOR THE EXACT SAME EXCHANGES! Different tournament formats produce different results for the exact same fighting.

Fighter Types

Let’s catch up with one of our many stickman friends, Alan Afterblow.

By some crazy magic Alan can never land the first hit on his opponent, but will always land an afterblow to the head. Since Alan lives in a country that fights exclusively full afterblow it works out great. It is literally not possible for Alan to lose a match fighting under these rules. He will always receive the maximum point value for every exchange. His opponents will always either tie or hit a lower valued target.

But Alan decides to travel a bit and enters a tournament where they use deductive afterblow scoring. Now he can never win single match! At best his afterblow can negate an opponent’s point, at worst it just decreases their score. He can never get points of his own.

He just went from 100% wins to 100% losses!

Alan has a sister, Nancy Nictabzug (they were separated at birth).

Nancy has equally crazy magic, she will always hit first, and always receive an afterblow to a higher value target. Unlike Alan, Nancy always loses under full afterblow rules.

But also unlike Alan she loves traveling to deductive afterblow tournaments. She can’t lose! At the worst she gets her attack negated, at best she hits a high point target and still gets points after the deduction.

Was this example a little crazy? Yes. But it’s the most extreme illustration of how a fencer can behave the exact same way in two different rulesets and have drastically different results. A good fencer will have skills to adapt to their environment*, and there are many fencers who make a point of exposing themselves to as much as possible to broaden their skills. But a fencer who only competes in a single region may well have a fighting style that is tuned to winning under their rules, and have a rating that reflects that.

*though there is another argument to be made that if your fencing needs to be changed significantly there is a problem with you, the rules, or both…

Conclusion

As I said at the start, this isn’t some exposé bombshell on the state of HEMA Ratings. At the end of the day HEMA Ratings can only work with the data they are given, and they have to expend an inordinate amount of effort to get something useable out of that. As I’ve worked out in the past, HEMA Ratings is a fairly good predictor of who is going to win a match. (HEMA Ratings – Does it actually mean anything?)

So nothing I’ve said here should really change how you feel about the whole HEMA Ratings project, but…