When discussing the stiffness of swords, it isn’t a big surprise that the term ‘safe’ appears fairly regularly. And, when you take a step back and think about actually trying to solve safety problems, we should be a little more measured in use of the term. Safe is a word that is, well, ‘safe’ to use. No one is against safe training swords, so it is hard to argue against. But the word itself is rather meaningless. Saying safe/unsafe is fine in colloquial usage, but if you are producing objective standards you need to do a much better job of defining it.

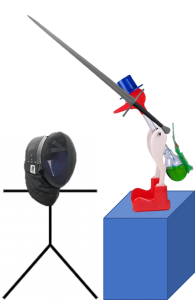

I will be using “performance” as a stand-in for whatever quantitative qualities of a sword (or safety equipment) are being measured. If you are looking at determining a reasonable safety in the thrust, the performance would be the stiffness, or compliance,* of the blade – as measured in newtons per meter, or collapsed into some sort of “index value” to make it easier to understand.

*Compliance is the opposite of stiffness. [Compliance] = 1/[Stiffness]

|

It seems that the most common scale to measure sword stiffness is what I call the FMC scale. Where swords are ranked according to:

Using the FMC you can very quickly contribute to any discussion by characterizing anyone doing something more intense than you as swinging crowbars, or less intense as using floppy swords! While intuitive, I think you can gather how helpful these terms are, and how meaningful a discussion they facilitate. |

Risk Assessment

Before you can decide what is safe, you need to have a defined level of risk. Generally the HEMA community has been pretty good at accepting risk being inherent to everything we do. And we should be. Every single thing you do has an associated risk, and if we fence, people will get injured. (Even if you just sit in a circle and read historical sources, someone is eventually going to roll their ankle in the parking lot.)

While there is a tacit understanding that there is some risk involved, there is almost no discussion on what that level of risk is! If you compare two established sports like FIE style fencing and ice hockey, you will see a very different accepted level of risk from acute trauma.

The current solution is that every event sets its own acceptable level of risk, and that is great. I personally am willing to open myself up to a fairly high level of risk in order to have a more intense competition. Many others who are doing HEMA prefer more assurance their body can come out as pristine as it went in. We can accommodate both. But ask yourself: when was the last time an event organizer communicated their thinking to the participants?

If your local scene is fairly homogeneous you may end up traveling to a tournament that is working under a fundamentally different risk assessment than what you assume. Best case is that you go away unsatisfied with the experience. Worse is if the event organizers or fellow competitors take issue with your behavior, because it doesn’t conform to their norms. And even worse yet is if an individual attends an event that is far more intense than they were prepared for.

Right now these are difficult things to attach numbers to, but if we never think about and discuss them, it will never get better. And if we ever want to have objective and empirical equipment standards we need some rational level of risk to compare the equipment’s performance against.

Further reading: For the paranoid and the pansies: What is real risk?

Injury Criteria

Even if you can articulate what an acceptable level of risk is, you can’t do anything meaningful without performance data. Imagine that we get a good database of the compliance of every HEMA sparring sword on the market. Then we do what?

Realistically what is going to happen is individuals are going to look at the list, pick the models of swords they would allow in their tournament and the ones they would not, and pick a number in between as the safety standard. Which is exactly what we are already doing!

In this case the number offers absolutely no added value (except in the case of quickly fitting in new sword models to the list). It is still the same intuitive understanding of what is safe, but now it has a quasi-mystical reverence because it is a number!

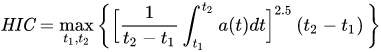

An injury criteria is a method of relating a certain circumstance to a likelihood of injury. Let us take the Head Injury Criterion (HIC) as an example. This is a number that expresses the likelihood of sustaining head injury from impact.

|

|

|

t2 – t1 = impact time |

a = acceleration in g’s |

The value of the HIC is then used to determine what the risk is. For example, the probability of different types of head injury that have been determined for an HIC of 1000:

|

HIC |

Severe |

Serious |

Moderate |

|

1000 |

18% |

55% |

90% |

This provides some method of determining how important different factors are into an injury. For a sword cut, what is more important: total mass or point of balance? What role does blade stiffness play? No one can answer these questions, so it is exceedingly difficult to determine what numbers you want to keep track of when evaluating performance.

And This Means?

You might think that this all seems like a lot of work. And you would be correct. This data doesn’t just appear by thinking about it really hard. It needs time, effort, data collection, and experimentation. And being clever. After all the very reliable “hit someone until they are injured” method of science hasn’t been in vogue for quite some time.

Will this data be ready by the time people start using numbers to set safety standards? No, probably not. But if we don’t start now, it never will be. Before we rush off to throw some numbers on paper to make us feel warm and cozy, we need to take a step back and think about what the numbers mean, and how they will be applied.

Addendum:

After reading through this, I realize that some people are going to take this as me advocating for:

- A rebuke of the community trending towards more flexible sparring swords.

- A call to start to quantify the damage caused by overly stiff swords, so we can have more forgiving trainers.

While this is an interesting rorschach test for the reader, this article doesn’t advocate any particular change in blade design. It is a call for understanding swords, and a suggestion that we are on the dumb side of the Dunning-Kruger curve in regards to our knowledge about blade interactions and safety.