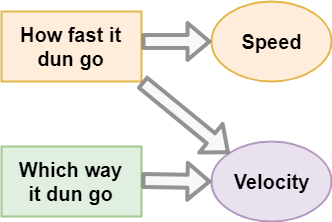

Vectors are used to quantify just about everything in life. Velocity, Force, Acceleration, Electrical Current, Heat Flow; these are all vectors. And the defining feature of a vector is that it has both:

- Magnitude (how much/big)

- Direction

Speed is a scalar, it’s a magnitude without a direction. Once we specify direction it becomes a vector. Fun fact: even money is often expressed as a vector! Though we don’t realize it, the cash flow becomes a vector once you add +/- to indicate to/from you.

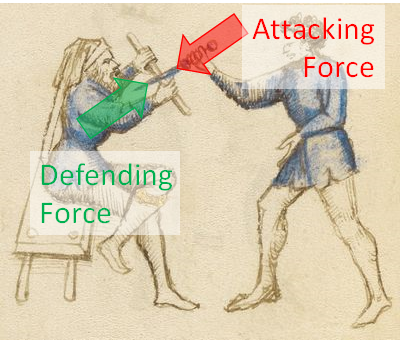

Force Vector: More than a science-ey sounding name

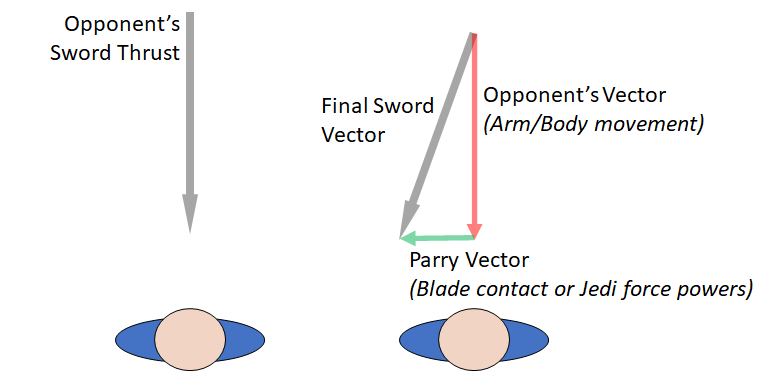

Vectors and Parries

If an opponent is moving a sword towards your head, their blade has a velocity vector. This has a magnitude (fast) and a direction (towards your head). Which gives us two options to avoid our impending doom*:

- Lower the magnitude to a safe speed (typically zero)

- Change the direction to a safe place (typically not your head)

*assuming we are too fat and/or lazy to move our head/body out of the way.

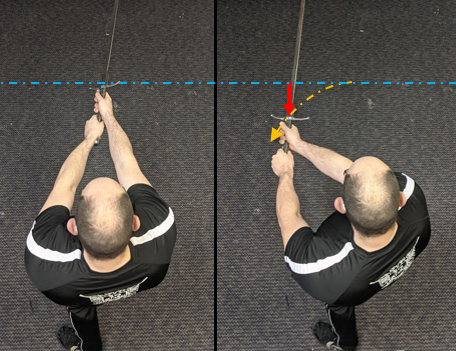

I’m using sciencey sounding words, but these options are very familiar to us. Changing the magnitude of the force to zero is commonly known as a straight parry, and it’s when you bring the opponent’s blade to a complete stop. In this case you must provide a force directly against the opponent’s line of action to decelerate their attack.

The option to change the direction of their velocity is done by diverting their blade to the side. This is most obvious in a thrust. It is very rare that one defends against a thrust by stopping it; instead the point of the sword is directed offline by applying force across the path of motion.

Cross-Contamination

It is highly unlikely that we are ever doing a pure magnitude or direction transformation on our opponent’s attack. This would require perfect alignment, which doesn’t lend itself well to spur of the moment actions. When performing a hanging parry we typically want to shed the opponent’s sword to the side, which is a transformation of direction. But you’ll still take some of the force on the blade, which means you’re also doing a magnitude transformation. How much depends on the exact geometry of the attack/parry.

Cross-contaminating between the two transformations can oftentimes be advantageous. A “hard” stop of someone’s blade or arm is certainly a change of magnitude type of block. But by slightly changing the direction you apply the force in, you can drastically reduce the magnitude of force they can bring to bear. This isn’t the same as changing the direction of their vector, it’s more changing the direction of your vector, which results in a decrease in their magnitude (fencing is complicated).

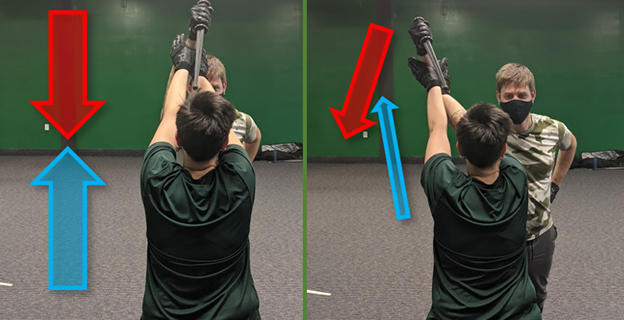

Constraining and Wedges

Vectors are fundamental to a proper mathematical description of motion, but most of the time we don’t have to think about them to get done what we want done. Thinking about vectors when you do hanging parries or dagger blocks is interesting, but might not add that much. One area where a little thought of vectors can be helpful is in understanding constraining and thrusting mechanics.

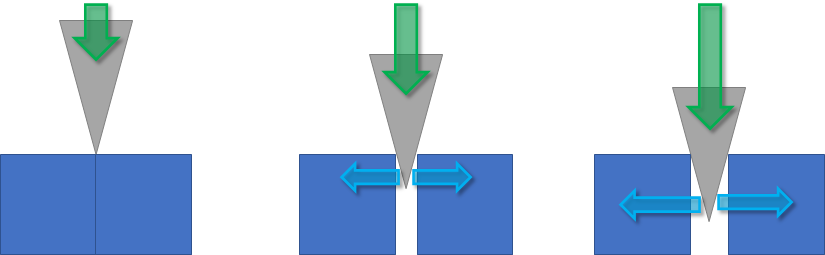

A common (and sub-optimal) method of constraining a blade is to push the opponent’s blade laterally until they are offline, and then move forwards.

In contrast to the push-then-move approach is a wedge. In this case you create a “wedge” structure which drives their blade to the side as you advance. The advantage being that you’re no longer chasing their blade, but driving directly in on the attack.

SwordSTEM isn’t a coaching blog, so I won’t go into the tactical pros and cons of each. But you should recognize the difference between the push-then-attack approach and the wedge approach. Just fill in the blanks to find out what the implications are for you.

Cone Arc(?)of Defence

Addendum to me not talking about the pros and cons of different types of constrainment: there is one geometric factor that many people fail to realize. And geometry is just the type of stuff I do talk about in these articles.

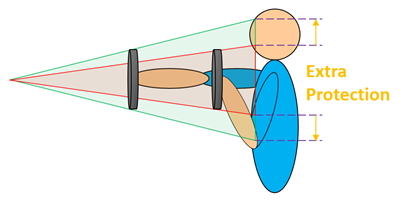

We’re already familiar with the concept of “Cone of Defence” from sword and buckler (Geometry Grab Bag).

But the concept doesn’t just apply to bucklers, it applies to swords too! As you extend your sword further in front, you will deflect the opponent’s blade considerably more than if you have the sword more retracted. And the more you push your blade to the side, the closer it brings it to you!

This means that you require comparatively smaller lateral displacements when the blade is fully extended. Something that you have to temper against the fact that your absolute range of motion is limited (Once again, not a coaching blog.)

Wrapping It All Up

Once you start imagining all of your fencing actions as vector transformations, you can start to see blade interactions in a different light. If you want to really challenge yourself, pick a few plays to work through while keeping track of every force vector you and your partner are transforming (Your feet on the floor count too!).