Balance is generally regarded as a very important part of any martial art. And for good reason. If you don’t have your balance stabilized you can’t effectively exert force using your body. And, it should be noted, we need to exert force to do anything. You exert force on your opponent to harm them and you exert force on the ground to move around.

Static & Dynamic Balance

It is an extremely pervasive traditional martial arts trope to imagine the master perched in a precarious position, completely stable and in a deep state of meditation. Such an image clearly communicates about how much mastery they have, and how they have developed command of their balance to superhuman levels.

But have they?

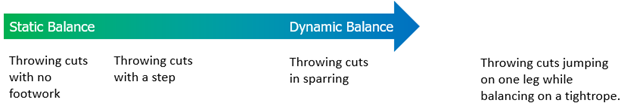

The human body has two types of balance, Static and Dynamic. As you can guess, static is the balance that is required to hold you in a position, like our aforementioned martial arts master. Dynamic balance is the skill required to stabilize yourself while the body is in motion.

| Static Balance | Dynamic Balance |

| Standing Still | Running |

| Balancing on one leg | Landing on one leg after a springing step. |

| Holding yourself in a lunge | Landing/recovering a lunge |

Like all movement quantities this is going to be scalar depending on just how dynamic the activity is. If you are moving slowly the activity is much less dynamic than if you are moving quickly.

Static vs Dynamic Balance

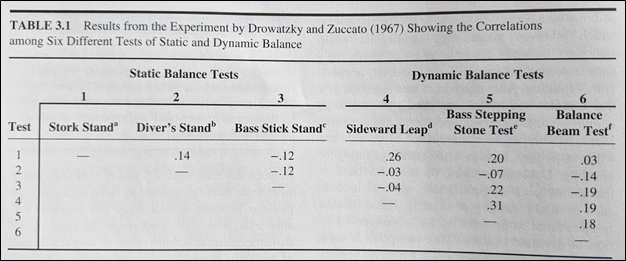

It is common to conflate static balance with dynamic balance into an overall balance ‘superskill’. However research has shown that this is quite simply not the case. As far back as 1967 we can see clear evidence that the two are not connected. In a study comparing the performance on different balance tests the researchers Drowatzky and Zuccato showed that there is an extremely low correlation between the two.

As a matter of fact, we aren’t even seeing a high degree of correlation between all the different dynamic balance tests! This result wasn’t a one-off; study after study shows that when you subject people to different balance tests you get different results. Summed up in the abstract to “Evaluation of the Specificity of Selected Dynamic Balance Tests. Perceptual and Motor Skills”:

“Many researchers have suggested that balance is not a general motor ability but rather is specific to the task which is performed. The purpose of the present study was to examine the relationship between a laboratory test (stabilometer) for assessing dynamic balance and three field tests: the Modified Bass Test, Balance Beam Speed Test 1 (forward walking), and Balance Beam Speed Test 2 (sideward walking). In addition, associations of whole body reaction time with scores of the four tests of dynamic balance were assessed in 54 undergraduate students. Pearson coefficient of determination indicated no significant correlation between the time participants were in balance on the stabilometer and on any of the three field tests. Body reaction time was significantly correlated with scores on the four tests. These results give further support to the specific character of dynamic balance since all tests seemed to measure different aspects.”

(emphasis added by me, because you probably didn’t want to read the whole thing)

Wait a minute…

You may have noticed that the results above suggest that not only are dynamic and static balance not related to each other, but that they are not even internally consistent. Which is very much the case. All research to date points to the fact that there is no general ‘balance’ skill. For instance the Berg Balance Scale requires 14 different balance tasks to be performed, each investigating a different balance parameter.

What does this mean for you?

A lot of times the information gleaned from sport science research can be somewhat on the academic side. So what does this all mean to a HEMA practitioner?

The long and short of it is (and remember Sword STEM is not a coaching blog!):

1) Don’t hope that static balance activities transfer over to your dynamic fencing activities. While I wouldn’t say this is exactly a common training method, it is good to know.

2) If you want to develop balance you have to have the training situation match your task as closely as possible. Doing a different activity, or at a very different speed, will not do that much to increase your ability to do the skills you actually need to fight.

As always, the upshot is that you need to train to match the actual situation you expect to be in. Go ahead and create specialized drills. They will enable you to develop skills much more readily, but be careful that you aren’t just training yourself to perform your specialized form of training.

Bibliography

Drowatzky JN, Zuccato FC. Interrelationships between selected measures of static and dynamic balance. Research Quarterly. 1967 Oct;38(3):509-510.

Tsigilis, N., Zachopoulou, E., & Mavridis, T. (2001). Evaluation of the Specificity of Selected Dynamic Balance Tests. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 92(3), 827–833. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.2001.92.3.827

Magil R., Anderson D., Motor Learning and Control – Concepts and Applications (11th).